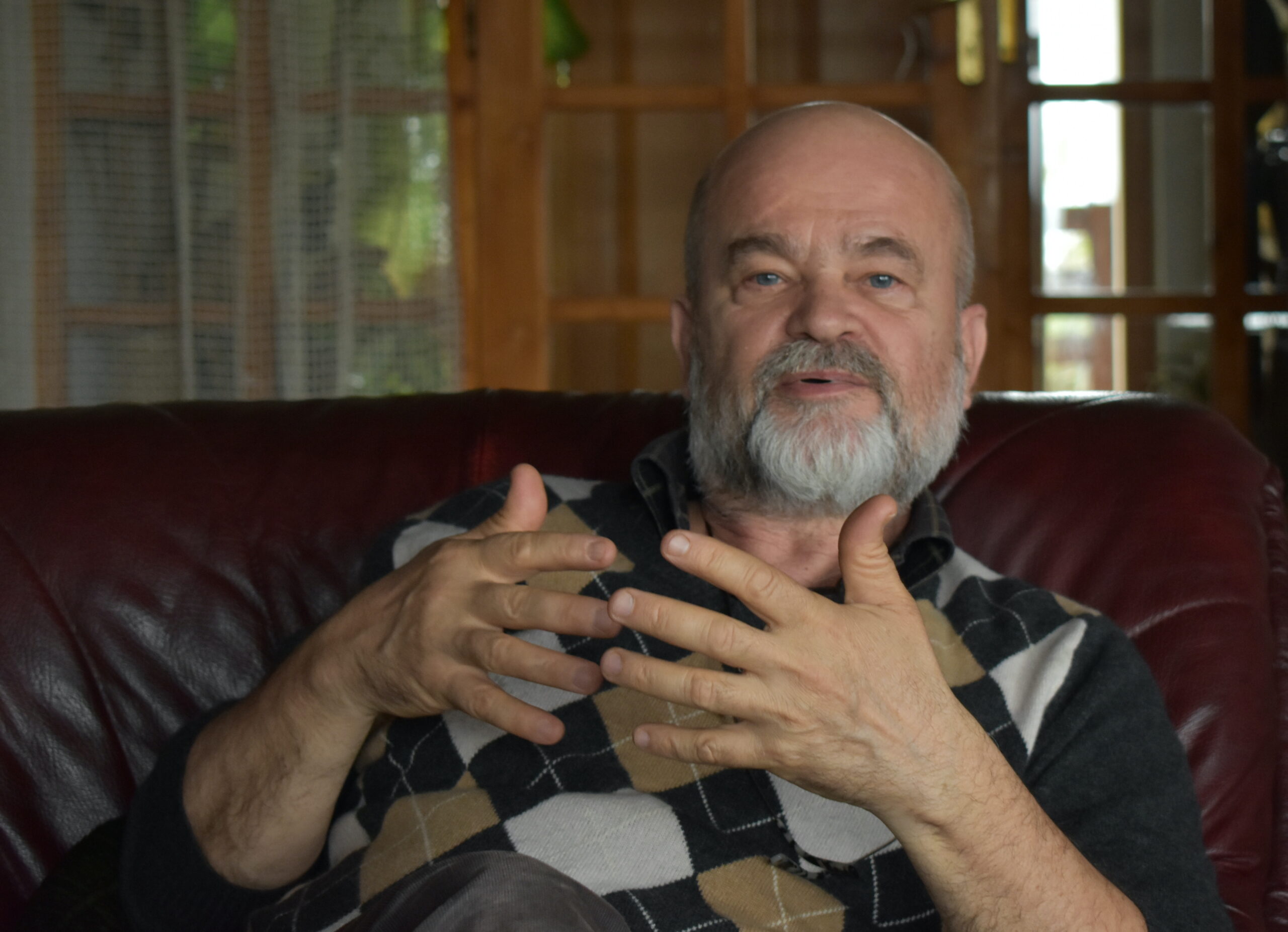

He was born in Bucharest, but a sudden turn of events propelled his parents to Marosvásárhely/Târgu Mureș, Transylvania. Dr. Sándor Madaras is mostly known for his work as a neurosurgeon, but people close to him admire his passion and knowledge in the field of folk art. As a doctor, he saves people’s lives, but as a private individual, he’s busy saving what’s left of the region’s traditions for posterity. After spending roughly five decades collecting traditional folk objects, he is now ready to show off the beauty and richness of the culture of this multicultural wonderland called Transylvania by exhibiting his private collection to the wider public in a new ethnographic museum established in Torboszló, Torba, Maros/Mures County. The museum will open its doors this June and exhibit more than 4,000 traditional folk objects from the region’s Szekler, Saxon and Romanian past.

“I can still smell the sun-bleached stones brought from the Küküllő river and laid in front of my grandparents’ house. This traditional house made out of loam had a special vibe, a warmth that I cannot forget.

I remember the area inside the house with that huge, traditional oven, which included an area where a thick woolen blanket was placed. That was the place for us kids. Each week, we ate up the traditional bread my grandmother baked, and that was also where we consumed all the traditional goodies such as a slice of bread with plum jam made by my grandparents. And people will never experience these treats again because they didn’t have the chance to live at that time,” Madaras tells TransylvaniaNOW.

The tastes, the smells, the vibes and the feelings, along with the traditional objects that surrounded Madaras as a child, have slowly vanished. The traditional items have been replaced by more practical alternatives, so the traditional space we knew underwent a slow but “deadly” transformation.

As the new objects found their way into the lives of Transylvanian villagers, the use of traditional objects and the whole lifestyle slowly went through a radical change — objects that had a long history of development based on usage were discarded for the sake of more practical new objects. For this reason, and because the younger generation didn’t find any use for the “old,” traditional items, they ended up in attics, basements or worse. That’s how these objects became things of the past, and now they are only part of the cultural memory.

“The folk art objects surrounding me were the result of lengthy development processes, both in terms of aesthetics and functionality. Modernization, on the other hand,

has sped up the processes, but that came at a cost.”

“Take the traditional pig slaughter, for example. In the old days it took about a day to process a 350-pound pig, to grind the meat and process it into sausage, but nowadays with an electric grinder, you can process that meat within an hour. But that meat and the sausages have lost their traditional taste,” Madaras explains to TransylvaniaNOW.

Rituals disappeared along with modernization, he reminds us, such as making a cup of coffee: The traditional way to have a good cup of coffee started with heating up the stove and then the water, adding the coffee, leaving it for a moment, and after that, filtering it before finally pouring a cup and enjoying the taste, he says. Now, you get a cup of coffee at the press of a button. But it tastes and feels different.

As he grew up, his love for traditional objects got stronger, and the road to becoming a collector began. Although at first it wasn’t a calculated move, it slowly became one as time went by. Madaras started collecting traditional folk objects at the early age of 16 because these items were the only ones he could afford, he says. Guided by practical aspects, when he went to Transylvania’s biggest antique and folk fair in Feketetó/Negreni, Madaras purchased his first object in his collection for a symbolic sum of RON 50: a woolen blanket that he found suitable for this bed. He was aware of the amount of work, material and sweat that had gone into that blanket, which he bought for such a small amount.

But more importantly, his teachers influenced him by introducing the folk art of other cultures to him. After getting to know these, he realized that “the objects and shapes he read and learned about are present in our culture, but they have been promoted more effectively,” he says. That’s how Madaras started hunting for traditional objects and acquiring them piece by piece.

The lifestyle that comes with collecting folk objects and art managed to infiltrate Madaras’ daily routine. “I do it because I like it, not because someone expects this from me,” he says. Madaras also spends time and money to restore and preserve the items he has saved from destruction. “The pieces I find usually aren’t in mint condition. There are some things I can repair; those I cannot, I take to professionals and museologists to restore them to their original condition,” Madaras explains.

The private ethnographic museum that Madaras and his wife Dóra Kristály are going to open to the wider public this summer in June is the result of a life-long collection.

“If you start collecting at the age of 16 and reach the age of 65, you find yourself in the situation where you’ve collected a lot of items. Since you can exhibit only a fraction of these items, they end up in boxes in the basement or the attic. But then you ask yourself the question: What’s the point of a collection that sits in boxes? The answer is: It doesn’t make sense. A collection only has a point and makes sense if it is shown, so exhibiting somewhere was the natural next step.”

After knocking on the door of several mayors in Szekler settlements, Madaras was surprised to find total apathy and rejection despite offering this collection for free. “But there was a lucky turn of events,” he explains, smiling.

“Why should I donate my collection to a museum that sits on lots of

objects without showing them?

So, I enrich their holdings with additional boxes? No.”

This is how the former Kakassy manor house owned by Madaras and his wife was chosen as the location for a new ethnographic museum of Transylvanian values, with a generous 350-square-meter multicultural space showing off the traditional values, rooms and objects of the Szekler, Saxon, and Romanian ethnicities populating this area.

Upon entering the museum, visitors will find three traditional rooms from an era that is now gone: a traditional Szekler kitchen, an altdeutsch (Old German) room, and finally a traditional Saxon living space.

The Szekler open kitchen includes a traditional beehive oven, a wood-burning stove and an eight-person table. This is a space where you can cook traditional Transylvanian food, Madaras says, diving into future plans to organize open events for those interested in truly Transylvanian cuisine.

The museum includes a rich collection of traditional ceramics, painted plates, pots, mugs, bowls, stove tiles, painted furniture, woven textiles, and more than 1,500 embroidered wall hangings with impressive motifs.

Along with the traditional rooms of people living in Transylvania, visitors will find the tools used by traditional craftsmen such as carpenters, coopers and blacksmiths, as well as the final products of these crafts. As in every museum, labels will guide visitors through the multicultural exhibit, but what makes it special is that the tour guide will be the owner of the collection, Dr. Sándor Madaras, in person. As the collector, he knows every object and will be ready to share their full story with those who pay a visit to the private ethnographic museum in Torboszló/Torba.

Title image: Part of the Saxon room in the ethnographic museum in Torboszló/Torba. Photo by: Antal Katyi