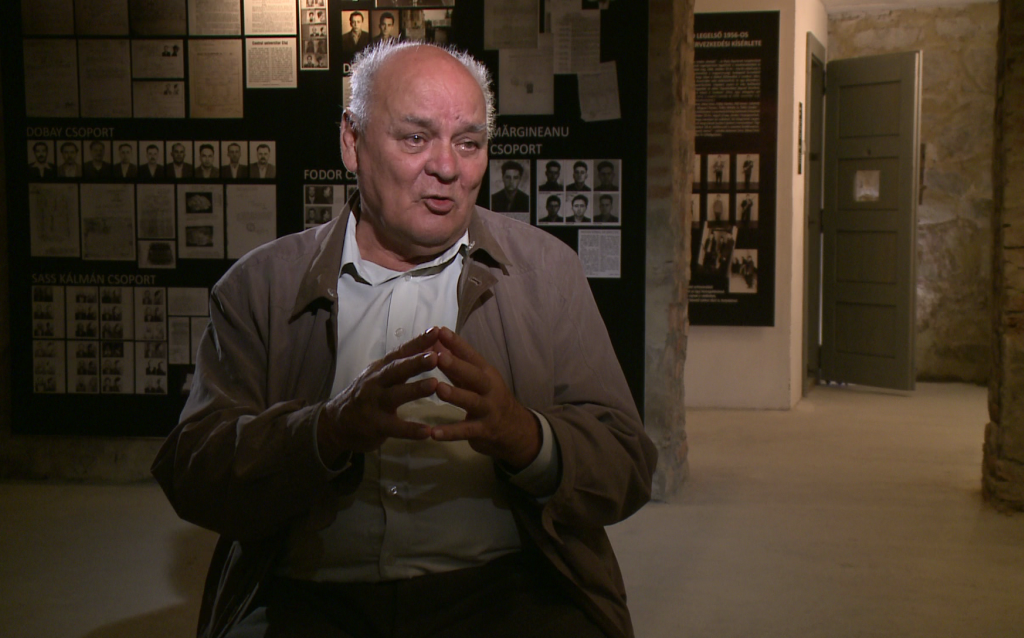

After hearing the news of the Hungarian revolution, 14 to 15-year-old students from the Székely Mikó Kollégium in Sepsiszentgyörgy/Sfântu Gheorghe founded their own organization: the Szekler Youngsters’ Fellowship (SZIT, Székely Ifjak Társasága in Hungarian). Later, on March 15, 1957, the group secretly laid a wreath on the monument of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution, which had no consequences. But when they repeated this gesture one year later, they got busted and caught. Members of the group received sentences of 6-18 years in prison and forced labor. One of the youngsters, Attila Bordás, who got 12 years, talked about the famous wreath laying and its consequences to documentary film maker Emese Vig three years ago.

After the Hungarian revolution broke out on October 23, 1956, many hundreds of kilometers from the Hungarian border, a couple of young students from the Székely Mikó Kollégium in Sepsiszentgyörgy decided that they had to do something. So they founded an organization, naming it the Szekler Youngsters’ Fellowship, and set the following goals: spreading the idealism of the revolution, fighting against the communist regime, and fighting for the survival of the Transylvanian-Hungarian community. The teenage boys even took an oath to uphold the above goals and started to organize secret meetings for themselves.

“We listened to Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America and waited for the demonstrations and then the fights to start in Transylvania as well. Even after the Soviet intervention in November, we didn’t want to believe that that was all. We jerked our heads up every time we heard some news from any kind of resistance and hoped that a small spark would be enough to restart the revolution. We heard about the new greetings of the revolutionists, the MUK (“Márciusban Újra Kezdjük” meaning “We’ll Start Over in March”), and we came to the conclusion that nothing was lost yet and the fight would soon continue. And when it happened, we would also be prepared.”

Successful wreathing, but cancelled revolution

The boys believed that the revolution would restart in March, so this is why they performed their first action on March 15, 1957. They laid a wreath on the monument of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution, which had broken out on that day against the Habsburg Empire, in the central park of the town.

“We definitely had to lay the wreath during the night when there were no pedestrians on the streets so that the next morning on March 15, people would be fully surprised. We couldn’t simply go to a flower shop to buy a wreath because we would have been busted immediately. But we solved this problem easily: We went out to the cemetery and put together one new wreath from the ones we found there. After dark, we ran down to the park. I jumped up to the monument’s pedestal and leaned the wreath against the plaque. We couldn’t even sleep that night because we were so excited to see the effect the next day. In the morning, I left for school earlier than usual, and of course I went first to Erzsébet park and passed by the monument. The wreath was there. Pedestrians glanced quickly at it but didn’t stop. And our secret hope that people would gather together and, after seeing our wreath, would be reminded of the idealism of the revolution and that something should be done just didn’t happen. The revolution was canceled.”

“We hurried up towards the monument. They were already waiting for us.”

One year later, on March 15, 1958, the boys tried to repeat the wreathing in the dark, but this time they got busted. Securitate agents were hiding and waiting for them everywhere in the park and even in the surrounding streets. So when the boys reached the monument with their wreath, they jumped out and caught them. There was no chance of escape.

6-18 years of prison and forced labor

The youngsters’ trial took place in Marosvásárhely/Târgu Mureș, and they were sentenced to 6-18 years of prison and forced labor. Attila Szalay was the one who received the most -18 years- despite the fact that he was not even a member of the group. He knew about its existence but was not a member since he was ten years older than the others. He was already in his mid-20s. But the Securitate needed an adult among the defendants, so this is why they involved him. Szalay didn’t survive the prison. He was beaten to death one year later in Szamosújvár/Gherla and died at the age of 29.

Attila Bordás was sentenced to 12 years and served his prison sentence in Ocnele Mari, Jilava, Nagyenyed/Aiud and Szamosújvár. In his interview, he said the following about the Jileava prison: “The hunger ruled there. I got so weak that I couldn’t even stand up on my feet. When I squatted down, I had to grab something in order to be able to stand back again. We didn’t stay there long either,because all the villagers from the area who were against collectivization were brought in, and the place got full. So we got transported.”

This was the time when they were transported back to Transylvania to Nagyenyed, where they were placed among common criminals who were there because of armed robbery or murder. “We were little bit afraid of them, but then we became friends because when they saw how thin and weak we were, they gave food to us from their own portions…. Those few months I spent there was a lifesaver for me. We were working in a metal industry factory in Nagyenyed, producing tens of thousands of padlocks.”

Lectures from cellmates

After he turned 18 in October 1959, Bordás was transferred to Szamosújvár, where he also had to suffer a lot of indignities:

“The usual punishment was that we were forced to spill out the water from our buckets to the concrete floor and then ordered to lay down on the wet floor on our stomach for half an hour, or one hour. After they let us stand up again, we didn’t get any more drinking water for the rest of that day. Instead we were left there freezing in our wet clothes until they dried out.”

The cells were very overcrowded, where two people had to sleep in one bed. But the fact was that 50-60 people were locked up in one cell and because of this a wide variety of people were forced to live together, which also had a positive side for a teenager:

“Most of them were intellectuals from different areas: army officers, doctors, priests, clerks. Most of them shared anti-communist and anti-collectivization views. … In order to pass the days more easily, competent people gave presentations about different subjects to the others. They taught us, youngsters mostly. I was learning German, history, and religious history from a Catholic priest and urban partisan fight tricks and other strategic techniques from an ex-cavalry general who fought in WWII around Arad and Debrecen. I even learned mathematics from him when we counted the trajectory of the cannon ball. I also learned about 150-200 poems – a mix of Áprily, Ady and Reményik. There were poets even among us, and we learned their poems too so that in case they wouldn’t survive captivity there would still be somebody left to remember their lines.“

“…I thought I wanted to die!”

After a while, Bordás was assigned to work in the prison’s furniture shop. Working day after day in the cold and drafty workshop, he got kidney inflammation, and so he had a constant urge to pee. The problem was that during his 10-hour shift, he was only allowed to go out to the toilet twice. One day, when he simply couldn’t hold it back, he sneaked out but got busted and beaten up very badly by one of the guards. Again… “I couldn’t sleep a minute during the night. There was no part of my body that didn’t hurt. And this was when – for the first time – I thought I wanted to die!”

A few days later because of “talking in line” he was punished again. But this time, instead of a beating, he got five days in solitary confinement: “This meant that I was put into the black hole where for two days my daily portion was 10 grams of bread and 1.5 liter salty warm water. Then for one day I received normal prison food, then only bread and water again for another two days. I was alone in the cell, and the guards even strung up my bed at five in the morning. So all I could do all day long – until 10 pm – was walk or stand. Five steps forward, five steps backwards.” He was not allowed to sit or lay down during the day, but it wouldn’t have been a good idea anyway because both the walls and the ground were dank in the cell.

“In the evening they gave me cattails, which I had to lay on the bed grid, as there was not even a mattress. And then within the cattails I found some polenta pieces. Somebody smuggled them there for me in order to not weaken completely. That time, I was still completely beaten up; my kidney was in continuous pain, and I was in a really bad condition overall.

…this small gesture shook me up. I was eating the polenta pieces and I was crying again, but this time because I knew somebody was taking care of me. Somebody wanted to help me. I didn’t want to die anymore. Live, survive; this is all I wanted now.”

Freedom smells like cinnamon

Attila Bordás was released on April 8, 1964. He was ordered to get on the first train and go to the nearest town, where he could change trains and go home to Sepsiszentgyörgy. After six long years, he was free again. He went to Dés/Dej first, and while he had to wait for his connection, he went into the town for a walk. Although he got back his original clothes, he had grown 10 cm during the past six years, so he outgrew all of them. His coat arms ended way above his wrists, for example, and his trouser legs were above his ankles. Moreover, he had two different shoes on his feet because the guards didn’t find his own in the storage room. So, he had to select from the shoes of the deceased and couldn’t find the right size in a pair.

“…beggars were better dressed than me when I started to walk on the streets of Dés. I felt that people were staring and laughing at me behind my back. I was a skin-and-bones, bald-shaven lanky boy in clothing that was two sizes too small staring at the streets, the pedestrians, and the buildings. A young woman standing front of a gate looked me up and down and went into her house. She returned quickly with a piece of apple pie wrapped in a napkin and handed it over to me. I hadn’t smelled the scent of cinnamon for six years…. But I couldn’t take the cake; I was very ashamed of myself. ‘Take it young man. I know where you are coming from. I lost my husband two years ago. He died in the Danube Delta,’ she said. And I started to cry. I was alive.”

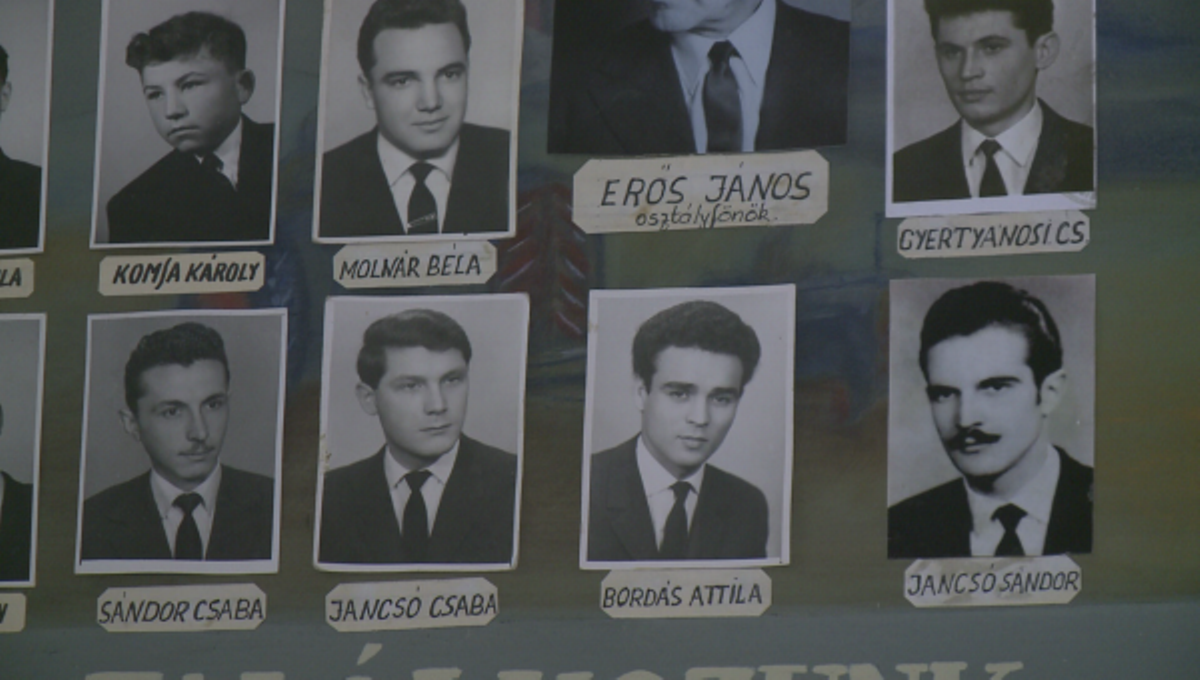

Attila Bordás is living in Sepsiszentgyörgy today. After his release, he finished his high school studies. Despite the fact that he didn’t graduate together with his Székely Mikó Kollégium classmates in 1959, his picture – just like the pictures of all the other Szekler Youngsters’ Fellowship members and their late head teacher, János Erőss – is in the graduation class photo. This was a tribute from their classmates to the bravery of the SZIT members. After finishing his studies, Attila worked in the Sepsiszentgyörgy Kombinat, where he also got to know his wife until his retirement. They have two children and three grandchildren.

Check out the previous parts of our “Lads of Transylvania” series as well: Part I.; Part II.; and Part IV.

Title image: 16-year old Attila Bordás and the Hungarian edition’s cover of the “Lads of Transylvania” book, which was published in 2018 and which contains the interviews with the still-living survivors of the Transylvanian Lads.