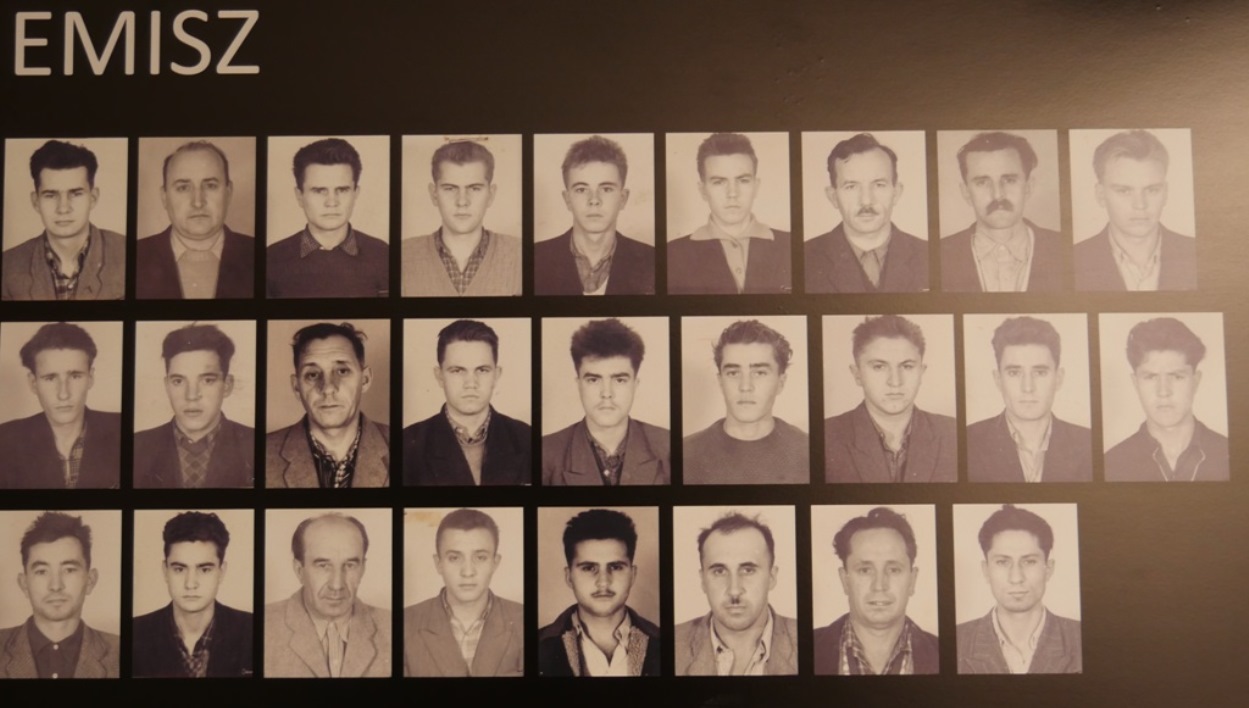

On November 4, 1956, exactly 63 years ago today, Soviet troops invaded Budapest and other parts of Hungary. Due to this, the Hungarian revolution against the Soviet occupation turned into a freedom fight. On the same day, 400 km from the Hungarian border in the easternmost corner of Transylvania in Brassó/Brasov, a few teenagers founded the Transylvanian Hungarian Youth Association (Erdélyi Magyar Ifjúsági Szövetség- EMISZ) after hearing the news of the Soviet invasion. Later, 77 EMISZ members were arrested and sentenced altogether to 940 years in prison and forced labor. Imre Lay – one of the founding members, who received 20 years – talked about EMISZ and his prison years to documentary film maker Emese Vig three years ago.

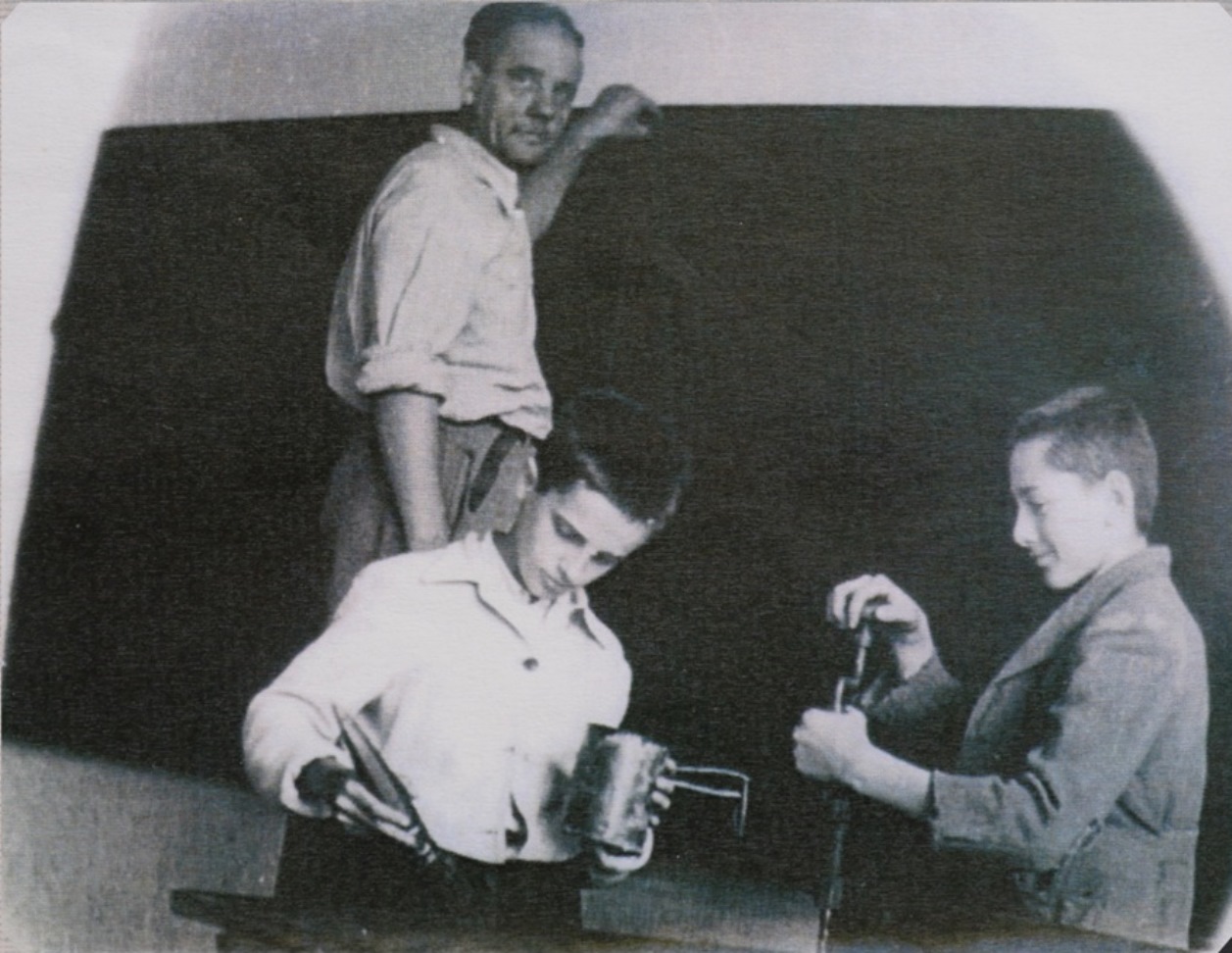

Imre Lay was born in 1938 in Brassó. Together with his younger brother, aside from school, he started to work alongside his father somewhere between the age of 10 and 12. He was only 16 when he already had a full-time job in a factory as an iron turner and was earning the same amount of money as his father. He continued his studies at night school. This was not unusual in his family, as he described:

“I’m from a working family. My ancestors migrated to Transylvania from Bavaria in the beginning of the 1700s. They first settled down around Temesvár/Timișoara/Temeswar then moved to Brassó. All of my ancestors were “Magyarized” Swabians; after WWI, my godfather was even imprisoned due to his Hungarian identity. My parents used to be involved in the organization of every Hungarian event in town, such as literary evenings, afternoon teas, and Hungarian concerts. They kept doing this despite it not being easy at all in those times because the Hungarians living in South Transylvania, which remained in Romania, had to suffer permanent atrocities. (Editor’s note: after the Second Vienna Award in August 1940, Northern Transylvania returned to Hungary, while South Transylvania remained in Romania.) Many of them even ran away from Brassó, but my parents did not. They stayed because my father was an indispensable repairman with a good salary in the Nivea factory.”

Visiting Budapest in the summer of ’56

“In the summer of ’56, we went to work with our father to Budapest … We could still see the marks of the war, but overall it was an impressive, European city. I was already surprised then at how big the difference was between the two countries. I didn’t notice anything about the upcoming revolution, but I was not even paying attention to that. I admired the technical novelties instead. The rear-engine Ikarus buses came out at that time, for example. We lived in Mátyásföld (suburb in Western part of Budapest) and became friends easily with the local lads; we went together with them to the Mátyásföld Ikarus factory’s club to watch movies. After work, we went to the cinema, to the amusement park in the City Park, and to the Palatinus open-air baths on Margaret Island. We didn’t notice any tension but only saw that people had a better life in Budapest than people at home. Than we came back to Brassó, and few weeks later we heard that the revolution had broken out…”

“We decided to found EMISZ on November 4”

“We were talking about the revolution all day long in the factory, and at school in the evening. We immediately thought that we also should do something, and our first thought was crossing the border – illegally – and joining the fight against the Soviet army. We wanted to help our Hungarian brothers and the revolution. But we dropped this idea fast because when we were coming home from Hungary, we saw how the border zone looked, with its high watch towers and armed guards with their dogs. We thought, why should we even try if it was impossible to achieve what we wanted? This is how the idea that instead we had to do something here at home started to take shape.

“Of course, we were following the news closely. There wasn’t a lot of radio in Brassó at that time; only every third street had one or two. We didn’t have one, for example, because during the war all the radios were collected, and when they gave them back, ours had been taken apart and was unusable … On our street, only one man – the butcher – had a radio, so we always went to his house to listen to (Hungarian) Kossuth Radio. On November 4, we heard that despite promising to leave, they had attacked Budapest at dawn. They were shooting in the streets, at the people, everything. This was when we decided to form our own organization, the EMISZ, the Transylvanian Hungarian Youth Association.”

The EMISZ was founded by five teenagers: Imre Lay and his younger brother György Lay, as well as Mihály Balogh Sipos, Ernő Mátyás, and László Orbán. Their first act was refusing to continue their Russian language studies. (Editor’s note: In the occupied countries, like Romania and Hungary, Russian language was obligatory for every elementary and high school student, even up until 1990.)

The group was expanding fast, and later they decided to reveal its existence to their favorite and most respected teacher and ask for his help. The Hungarian-French literature and grammar teacher Benedek Ópra was at first very surprised about the organization. But then he advised them to involve mainly the working class youngsters from the factories because they were the ones who had to be woken up to see what those in power were doing in their names.

“We wanted to create an organization that was against nobody but instead identified itself as a so-called labor organization. Basically, we saw the Young Transylvanian Hungarians’ labor organization in it, which was representing for real the interest of the Transylvanian Hungarian Youth instead of the communists’. The Brassó school students coming from the countryside did know exactly what was going on in their home villages and towns. They knew about the abuses and reported about a lot of complaints. They told us how the collectivization was taking place and how arbitrary the communist leaders were. We wrote down all of these complaints and after summarizing them, we wanted to pass them somehow to the international forums.”

The youngsters organized their gatherings in a small park in Brassó. Imre Lay even wrote an anthem for the organization, which was later put to music by the wife of the Unitarian pastor of Homoródkarácsonyfalva/Crăciunel/Krötschendorf. They also wrote an oath and swore to the EMISZ. Then in February 1957, they elected the leaders of the organization: “László Orbán became the president; Balázs Sándor, János Vinczi, and János Ambrus the vice-presidents; while I became the secretary and my brother the treasurer.”

Wreath laying at the 1848 monument of Fehéregyháza

“On March 15, 1957, we went to Fehéregyháza/Albești to celebrate the 1848 revolution’s anniversary, and we sang songs and recited poems by the monument, where Sándor Petőfi had disappeared. (Editor’s note: Petőfi is one of the most emblematic poets of the Hungarians who fought against the Habsburgs during the 1848-49 revolution and freedom fight and who lost his life during a battle at the young age of 26.) Laci Orbán gave a short speech about the importance of March 15, and compared it to October 23, 1956. Basically that was it; the whole thing was over within 1.5 hours. Everybody had a hidden cockade (Hungarian ribbon rose pin) with himself too. We always had. For example I even had mine with me in my “bulletin” (ID card), when I got arrested, and so I rather swallowed it then because I didn’t want them to find it. However, when we were reciting and singing, we saw some civilians stopping by and looking at us. But I only thought that they were locals.” The boys were so naive that didn’t even think that they could have been observed by Securitate agents.

After the wreath laying, as the time went by, the organization grew: “We already had a lot of members, but there were also many who had only heard about it and knew one or two EMISZ members, but hadn’t joined yet.

I don’t even know how we could have thought that the Securitate would not find out.

“And as it usually happens, we got busted because of something small, and not even when in ’57 two of our members (János Vinczi and Imre Erzse) tried to escape to Yugoslavia and got caught. The boys – before they left – had memorized the complaint list, which was collected by the EMISZ. Their plan was that after their successful escape, they would tell Western reporters and Hungarian emigrants about how we lived in Romania and that there was this new organization called EMISZ, which was trying to fight against the communists. But they were caught, deported back, and sentenced because of prohibited border-crossing. But none of them said a word about the organization or the complaint list during their interrogation. Securitate agents only came for us in following year, when an EMISZ letter – under still unclear circumstances – somehow ended up in their hands.”

“I thought, they will only frighten us, and then we can go home.”

“I thought, they will only frighten us, and then we can go home. But it didn’t happen like that. After eight months of interrogation, I was sentenced to 20 years of forced labor. I was arrested on August 15, 1958. I was working together with my father: We were whitewashing a house at the end of Mihai Vitazul street.

Around noon, my father asked me to go home and bring him lunch. I was hurrying and didn’t even say goodbye to him because we were going to meet again in half an hour anyway. That was the last time I saw him alive.

“When I got home from prison (editor’s note: six years later), my mother welcomed me sobbing and said: ‘We buried your father yesterday.’”

Securitate lured Imre Lay from his home by lying to him that they were police officers who only wanted to ask him a few questions about an accident that had just happened in the factory where he was working. After three days of interrogation and a heavy beating, they put him into the same cell with the Evangelical priest of Brassó’s famous Black Church, Konrad Möckel:

“Don’t expect anything good from them, he said to me. They won’t let you go home, that is sure. If it turns out that you were a member of an organization, the least you can expect is 15 years in prison.

Then he told me that most probably he was going to get even more and that there were also youngsters in his group. They didn’t want anything more than to achieve some rights for the German minority.” -The priest first taught the Hail Mary in German to Lay, who then was already studying the basic German vocabulary with Möckel, when he got transported to Marosvásárhely/Târgu Mureș for his trial.

The verdict: “conspiracy against the social order”

The interrogation reports contained such ridiculous lies, for example, that the EMISZ members wanted to blow up factories, poison wells, etc. Using these lies, Securitate officials wanted to accuse the boys of terrorism, for which they could even get the death penalty. But fortunately this did not happen, and “Conspiracy against the social order” was written in the justification of their verdict. The trial took place on March 19, 1958, and György Lay received 20 years of forced labor, while the 77 EMISZ members altogether got 940 years.

Before his transportation to the Szamosújvár/Gherla prison, Lay even got a 12-kg fetter as a “farewell gift” from one of the guards who especially didn’t like him: “This is how I was pushed into the cell where the other inmates were waiting until their transportation, and when I entered I saw a familiar face; it was our teacher Benedek Ópra. I stayed at the door, because I was so ashamed. This was the hardest moment of my life because I realized then that this clever, brave, and valuable man – who even had a family – was chained up because of us. I didn’t even dare to approach him, but meanwhile I saw that Uncle Benci was hugging the boys and was talking with them. When he glimpsed me, he asked me to go there as well, and I slowly walked to him with the fetter on my legs. I was standing ashamed in front of him, but he hugged me and encouraged us: “I am not mad at you boys,” he said. Unfortunately, he died 10-12 years after his release, but I still visit his home village, Kézdiszárazpatak/Valea Seacă when they call me because we have a “kopjafa” (editor’s note: traditional Szekler memory pillar usually made out of wood.) there too. The local school is also named after him.”

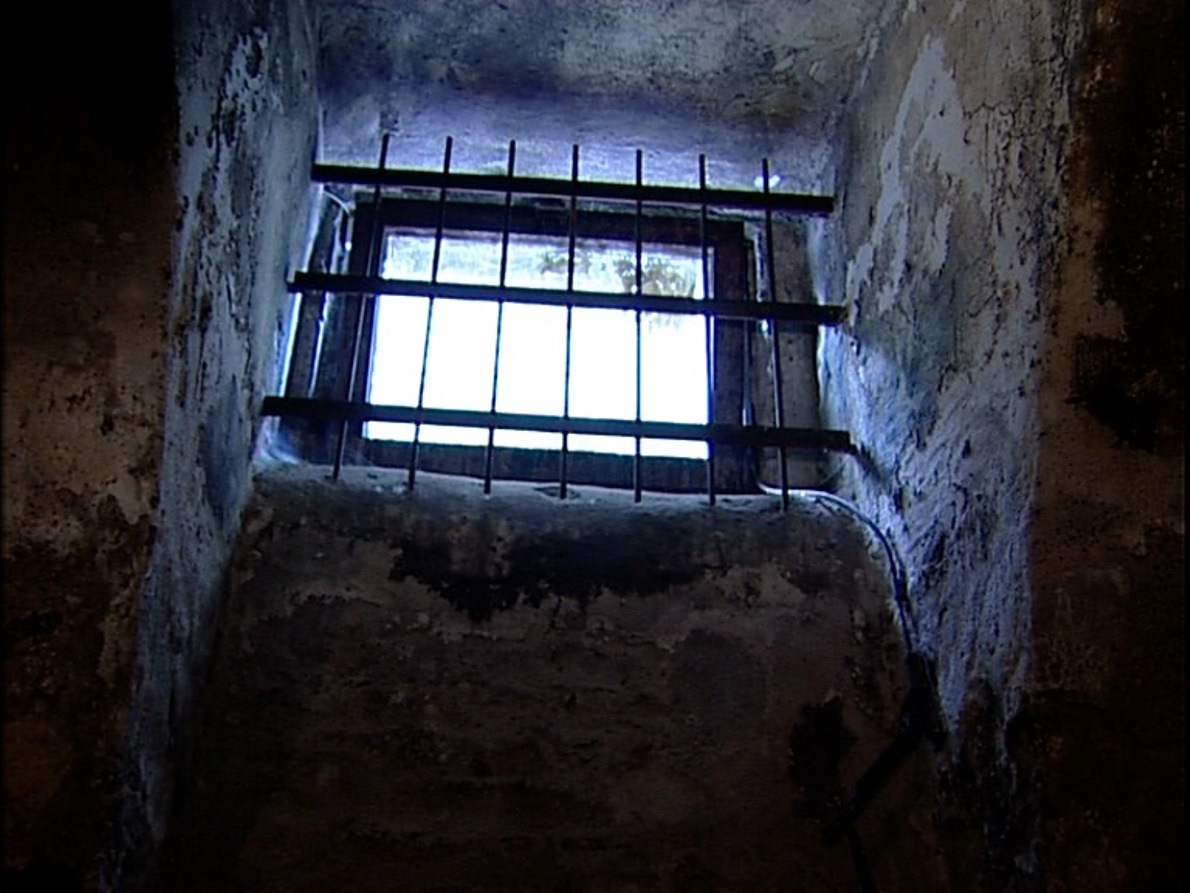

György Lay and his mates were transported to Szamosújvár, where among others, for example, Árpád Csaba Józsa, Árpád Szilágyi, and Attila Bordás was imprisoned too. The overcrowded prison with its yellow walls was simply called the “yellow crematorium” by the Brassó youngsters because many of the inmates died due to the inhuman conditions and permanent beatings and torment by the guards:

“They shouted into the cell, ‘Sub pat, fuga mars!/Under the bed, now!.’ But we had bunk beds with three or four levels, so not everybody could fit under them. Each time some stayed out, and the guards always beat these ones up with their truncheons. We tried to pay attention to each other and rotate ourselves in order to avoid that always the same people would stay outside and get the beatings.

Other times they locked us up into the shower, and first sluiced hot – almost boiling – then ice-cold water over us. Meanwhile they were just sitting outside and were laughing at us as we were screaming.”

“There were about two hundred guards at Szamosújvár during our time, and 12-14 of them were real bloodthirsty bastards, of whom even the other 180 guards were more afraid than us, who were young then and had nothing to loose.” But even under such inhumane conditions, the boys had some positive experiences as well:

“In the prison, a very human relationship was formed between us and the Romanian inmates. I had a feeling that they surrounded us Hungarians with love and sympathy because of 1956, which was really nice.

“About 1,200 inmates were working in the Szamosújvár furniture factory, and only 70-80 of us were Hungarians. A lot of Romanians got imprisoned also because of 1956, hence they were organizing themselves against communism too, just like we did. I got to know in the Szamosújvár prison the Boicu brothers, Vlad and Nicolae, for example, and there was also a boy named Hamza. They were talking about us all the time as a positive example; that look what the Hungarians dared to do.“

The number of intellectuals was high among the inmates, and so they were teaching the youngsters: “I learned a lot of things there. As much as I didn’t like studying when I was free, I was absorbing knowledge like a sponge in the prison from those wise people. As I like to say, I finished university in prison.”

“We were the last to be released on June 30, 1964. (Editors note: political prisoners in Romania received general amnesty in 1964.) It was Friday when we got home. Our mother greeted us in mourning. She had buried our father one day earlier.

“I’ve still been fulfilling the duties of the EMISZ secretary ever since. I keep contact with the members; I ring everybody up at least once a year to check out who is still alive. Out of the 77 imprisoned EMISZ members, 43 have passed away already. I also wrote a poem in their memory…which I recite each year on November 4, on the anniversary of the EMISZ foundation. Maybe they can hear it.:

Our “Lads of Transylvania” series is over for this year. Check out the previous parts as well in case you haven’t read them yet!: Part I; Part II.; and Part III

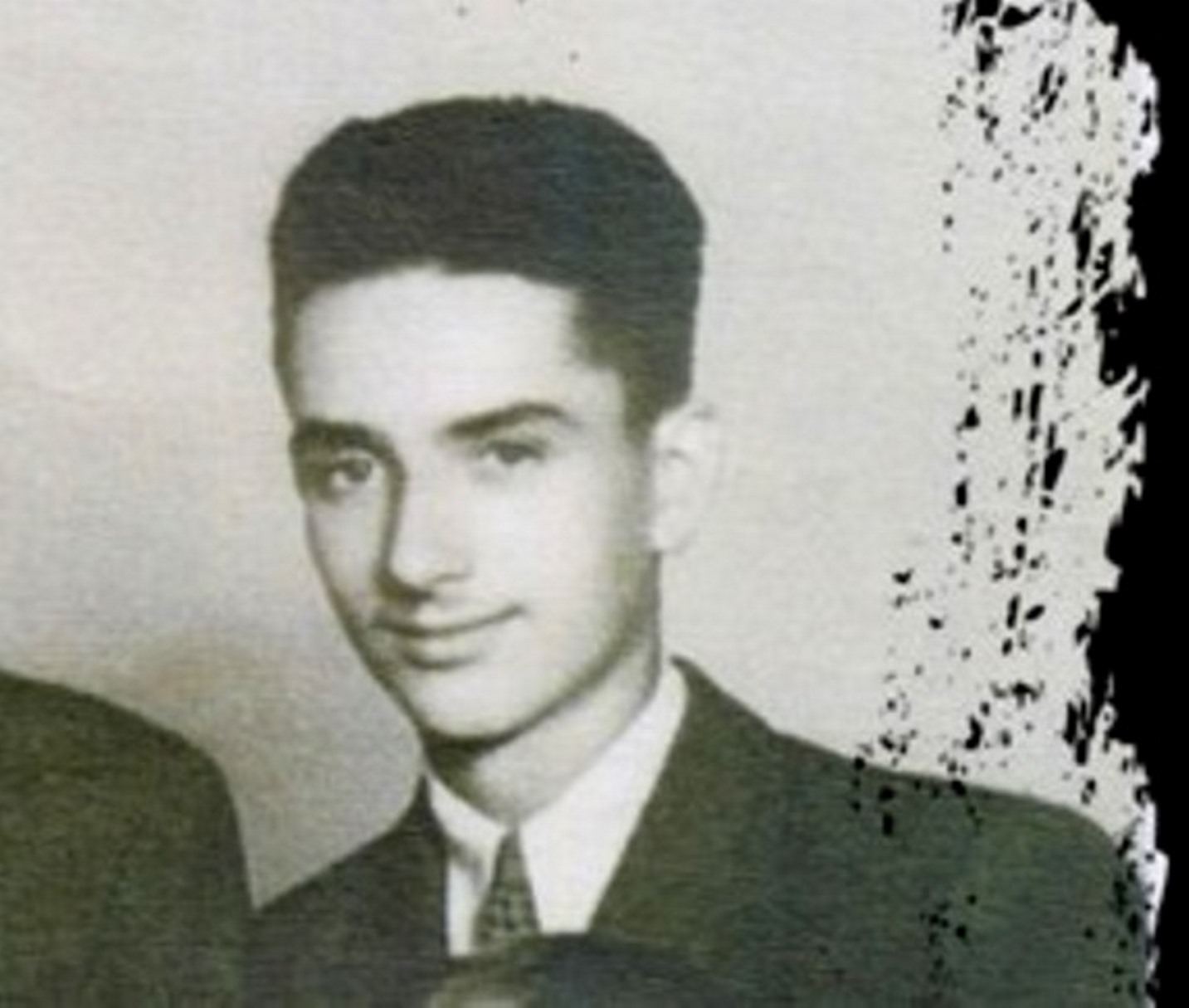

Title image: The young Imre Lay before his arrest and the Hungarian edition cover of the “Lads of Transylvania” book, which was published in 2018 and which contains the interviews with the still-living survivors of the Transylvanian Lads.