“Lads of Pest” (pesti srácok in Hungarian) were those youngsters in Budapest, mostly in their teens or early twenties, who took up arms to fight against the Soviet occupation in the Hungarian revolution and freedom fight starting on October 23, 1956. Young Transylvanian-Hungarians were also informed about these events, and even though they did not spring to arms – they didn’t even have the chance to do so in Romania – many of them openly showed their sympathy for the revolution in several forms. Some of them lighted candles, others secretly laid a wreath during the night, somebody wrote a letter to a Hungarian Magazine only to give his warmest support. But there were boys who even crossed the green border to join the revolutionaries and fight against the Soviets. These teenagers – or youngsters in their early twenties – later got imprisoned and tortured for years in the Romanian prison system for their brave solidarity. Due to the persecutions and humiliations, one of them even committed suicide by setting himself on fire in front of the communist party headquarters in Brassó/Brasov. These youngsters deserve to be remembered and they also deserve to bear the name of “Lads of Transylvania” similar to their fellows in Budapest. Last year an book of interviews with survivors who were still living was published under the title of “Lads of Transylvania,” and in the forthcoming days we are going to share the shortened versions of the book’s four interviews. Here comes the first one:

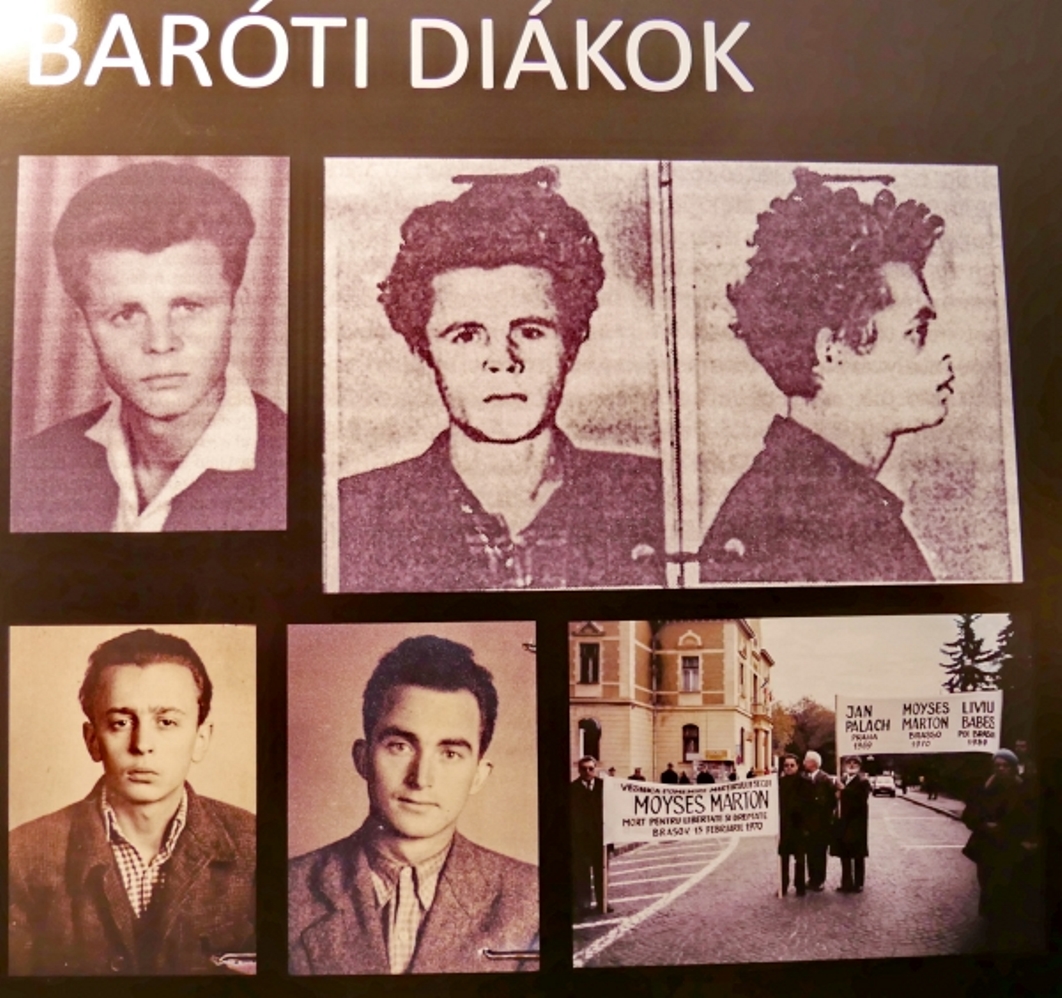

In October 1956, Transylvanian Hungarians were closely listening the Hungarian radio and were following the happenings of the Hungarian revolution. Young and old, adults and students excitedly waited for the good news. But the initial enthusiasm was soon replaced by worry and then with grief. The revolution was beaten down. But maybe there was still something what could be done. On November 4, four Szekler high school students in Barót/Baraolt decided to flee over the border, join the revolutionists, and start to fight against the Soviets.

After hearing the news on the radio, one of the teachers of the Barót high school dormitory, Csaba Dénes, told to his students that a revolution had broken out in Budapest. “We were proud to be Hungarians even before that. But hearing this news, we started to talk about how nice it would be if we could also be in Budapest.” –tells Árpád Csaba Józsa in the book. At the time, he was just a 16-year-old 10th grader. “Benjamin Bíró, János Kovács, Márton Moyses, and I were talking every day about what we could do. The teacher also told us that boys the same age as us were also fighting on the streets of Budapest with weapons in their hands. This is how days were passing by until November 4, when Csaba Dénes came with the news that the Soviet army had flooded Hungary. We had the feeling that it didn’t mean any good, but we still didn’t think that it was only a matter of days that the revolution was going to be put down by the Soviets. We felt that this was the time when we had to do something, that this was the time we had to give a helping hand for the revolutionists. This is why we decided to cross the border no matter what was going to happen to us.”

The four friends got on a train on November 8 and traveled from Szeklerland to the Hungarian border. After getting close to the border, they got off the train and started walking towards the green border. The two older (16-year-old) boys, Józsa and Bíró, went in the front, while the 15-year-old Kovács and Moyses were following them at a 50-60 meters distance. They were wandering there already for two nights and two days when Józsa and Bíró realized that, although they got through the border finally, they had also lost the other two at the same time.

“I only got to know years later – after my release – what happened with our two mates. I met with Kovács in 1961, who honestly admitted that Moyses wanted to keep going in any case, but he was the one who convinced him to turn back because he felt they didn’t have any chance to make it to the other side. The night-long ramble in the cold and dark night discouraged him, and all he could think about was that they can only get out from this adventure as losers because they will be caught either by the Romanian or the Hungarian border patrol and they will end up in jail anyway.” –says Józsa in the interview.

Józsa and Bíró, using aliases and telling everybody that they were orphans from Szabadka, Yugoslavia, made it to Debrecen, where they first got arrested by the Hungarian police. But only a couple of days later, a delegation of the local workers’ council successfully freed them. They were placed in a workers dormitory where they met with some other youngsters who were planning to escape to Austria. They asked the two Szekler boys as well to join them, but they refused to leave. They reminded themselves that they didn’t come here to immigrate to the West but to stay in Hungary and to join the revolutionary activities. Despite the fact that they saw less and less chance for this scenario, they still decided to stay. Józsa started to work in a factory, and Bíró could even continue his studies in a local high school. In December, they even received a residence permit for one year. As the days and weeks slowly passed by, it seemed that they were not going to get busted and they could fit into their new life instead. On the other hand, it was crystal clear to them that they didn’t have a choice. They couldn’t go back to Romania because if they would, they would get arrested immediately.

But three months later on March 12, 1957, the boys were taken to the police station. They knew everything about them. They knew their real names, their real home address, their age, etc. They new everything, so there was no point of denial. Two days later, they were arrested and on March 15 escorted to the Hungarian-Romanian border where the Hungarian police handed them over to the Securitate. Because a Hungarian colonel had a statement saying that they were not involved in any “counterrevolutionary” acts (which was true anyway), instead of seven or eight years in prison, they “only” received sentences of three and three and a half years. The two 16-year-old boys were convicted in Nagyvárad/Oradea on May 17, 1957. They last saw each other in the court room that day and never ever met with each other again.

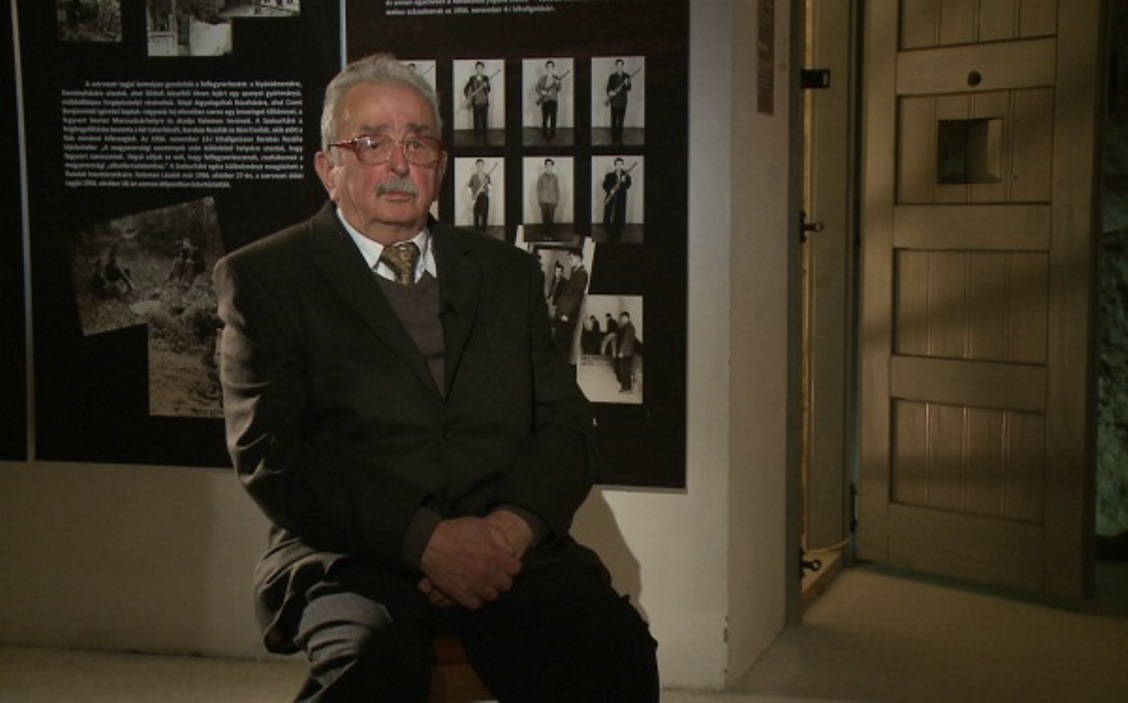

Józsa was released three years later from Szamosújvár/Gherla on March 17, 1960. In the interview, he remembers his mates from those six decades ago like this:

“Unfortunately, I am the only one still alive from my Barót mates. János Kovács, who finally didn’t cross the border to Hungary, used to work in Brassó, but passed away many years ago. I don’t know exactly what happened with Benjámin Bíró. I heard two rumors about him. One says that he was taken to the Danube Delta after the verdict, from where he tried to escape and was shot to death. The other rumor is that after his release he managed to escape to Yugoslavia. None of this information is verified. All I know for sure is that I last saw him in the court in Nagyvárad.

Márton Moyses, our fourth mate, was a very talented student. He just loved Hungarian literature, and he used to write poems himself as well, and this was the reason why he was brought to justice in 1960. The judge read one of his poems out loud. “Red and Black” was the title of it, and the judge asked him why did he write it? Moyses pointed out the window: “Your Honor, can you see that grey sparrow? That little bird is free…” Moyses got seven years. In the prison, torture was followed by torture. They kept interrogating him about his mates and because he wanted to avoid confessing against anybody, he instead cut off his own tongue with a thread. They sewed it back right then on the spot without any anesthetic.

He was already a human wreck when, following his release, he was deported to his forced domicile in Nagyajta/Aita Mare. He worked as an agriculture worker because despite his great skills, he couldn’t get any other kind of job. Then, on February 13, 1970, in front of the communist party headquarters in Brassó, he doused himself in gasoline and set himself on fire. The fire was put out, but Moyses had already suffered fatal injuries. Every kind of medical help was refused to him, so he had to suffer for three months in horrifying pain until he died finally at age of 29 on May 15. 1970. His poems, which were still available that time, were destroyed by the Securitate. This is all I know about my mates. Their memory should be blessed.”

Check out the other parts of our “Lads of Transylvania” series as well: Part II.; Part III.; Part IV.

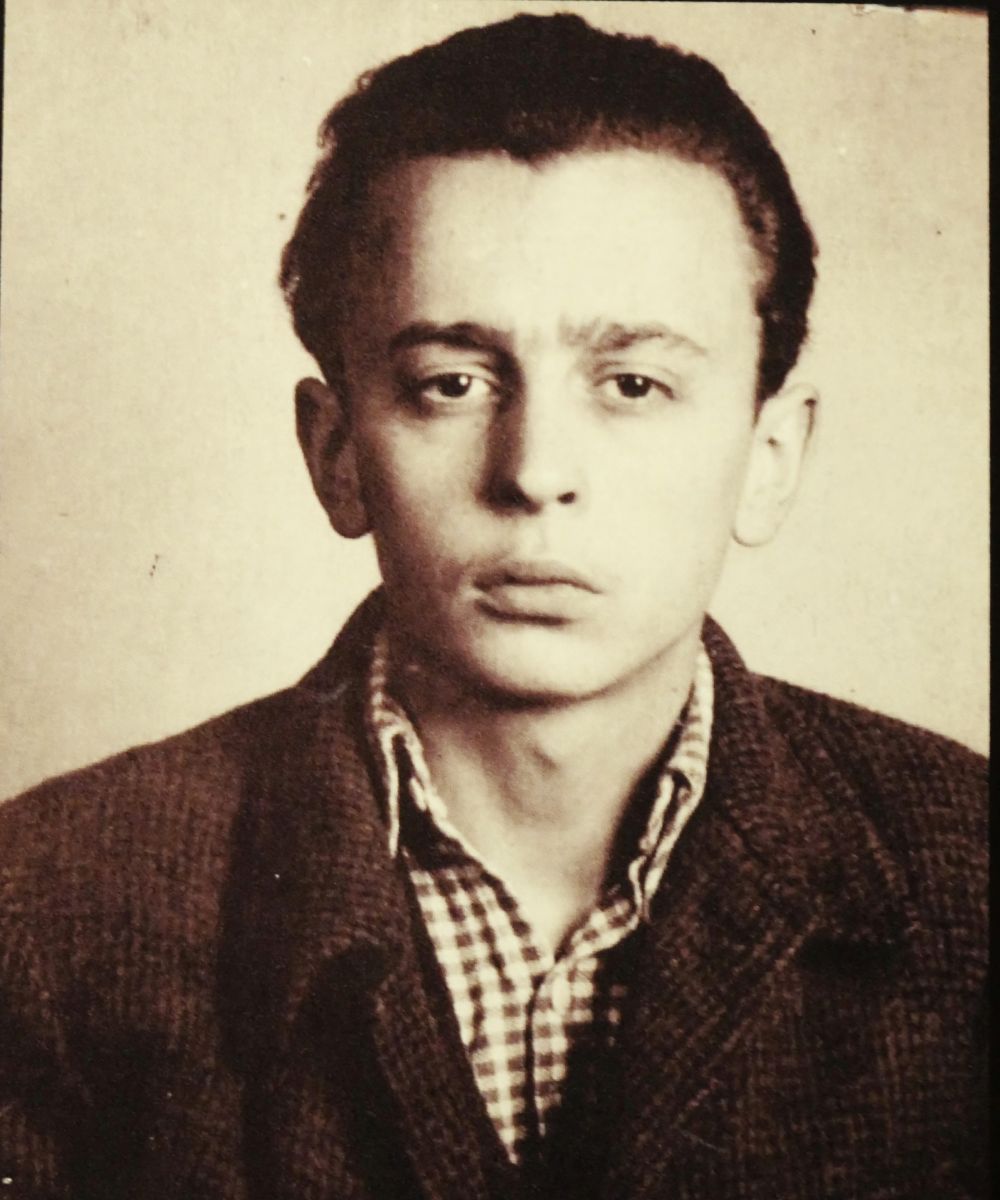

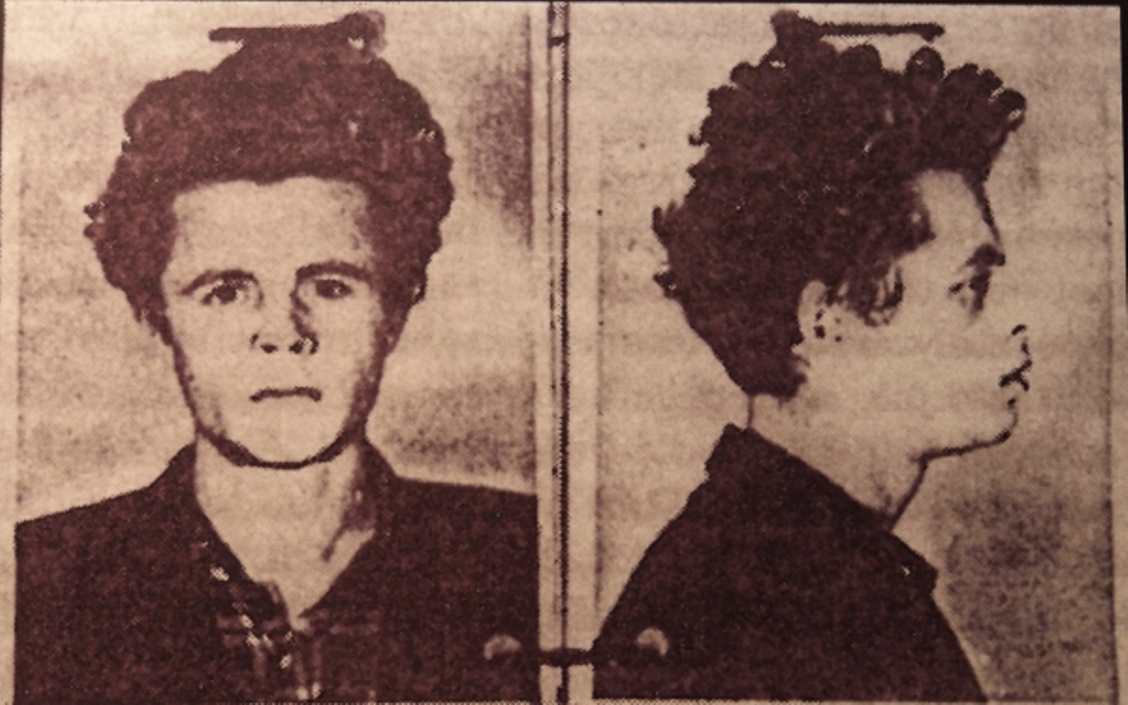

Title image: Three out of the four Barót Students. From left to right: Benjamin Bíró, Árpád Csaba Józsa, Márton Moyses and the cover of the “Erdélyi Srácok” book in the lover right corner.