Béla Markó (69) is an ethnic Hungarian politician, poet and writer from Transylvania. He has an impressive literary oeuvre, including over 40 volumes of poetry, plus prose, literary translations, journalism, essays and school textbooks. As a politician, he was the president of the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (known by its acronym of RMDSZ) between 1993-2011 and twice deputy prime minister (2004–2007 and 2009–2102). He recently received a lifetime achievement award from Hungary’s journalist association MUOSZ. TransylvaniaNow asked him about poetry and politics, in this order.

TransylvaniaNow – Let’s play a little game. What does Béla Markó the poet have to say on the futility of prizes?

Béla Markó – A prize won’t make anyone more or less. There are many examples both for good decisions and bad ones even from the awarding bodies of the most prestigious prizes. An award, however, does have the merit of drawing attention to the recipient. In the case of a writer, maybe people who have never read him will pick up one of his books. I would say being in the limelight is the main benefit of an award.

But even this can be a double-edged sword. I believe it was Socrates who recounted that when he asked Pericles why he doesn’t have a statue in Athens, he replied: Because it is better if they ask why I don’t have a statue than why I do have one. But jokes aside, recognition is important to every public figure. And professional awards are worth more than those given based on political criteria. I know what I am saying, as over the decades, I have both received awards and also given a few — the latter, not by myself.

TN – Good politicians never lie, but they never tell the whole truth either. A poet, on the other hand, must wear his heart on his sleeve. Is it a relief to be free of political burdens?

B.M. – In my experience, it is not only politicians who ponder — poets do as well. In this sense, the two are not that far apart. There are many things between the lines in a poem, and sometimes, what the poet doesn’t say is the really important part. The major difference is that a politician formulates an opinion worked out with others, or at least pays attention to what those around him think, meaning that he will be less original, less poignant and sometimes will even refrain from voicing his own opinion. This is why political statements are mostly colorless, bland and avoid hot topics.

Indeed, a politician in good standing doesn’t lie, but is not fully sincere either, sometimes simply because he doesn’t want to reveal his cards to his negotiating partners. When I got out of daily politics, it took me years to get rid of the political consideration as to what should be said and what should not. I think by now, I am almost there. It makes a great difference that when I express my opinion on something, I know many behind-the-scenes secrets about how politics works that others don’t, but now I can look at those things with the eye of a writer. Yes, it is liberating that I am no longer accountable to others, only to myself. And perhaps my readers.

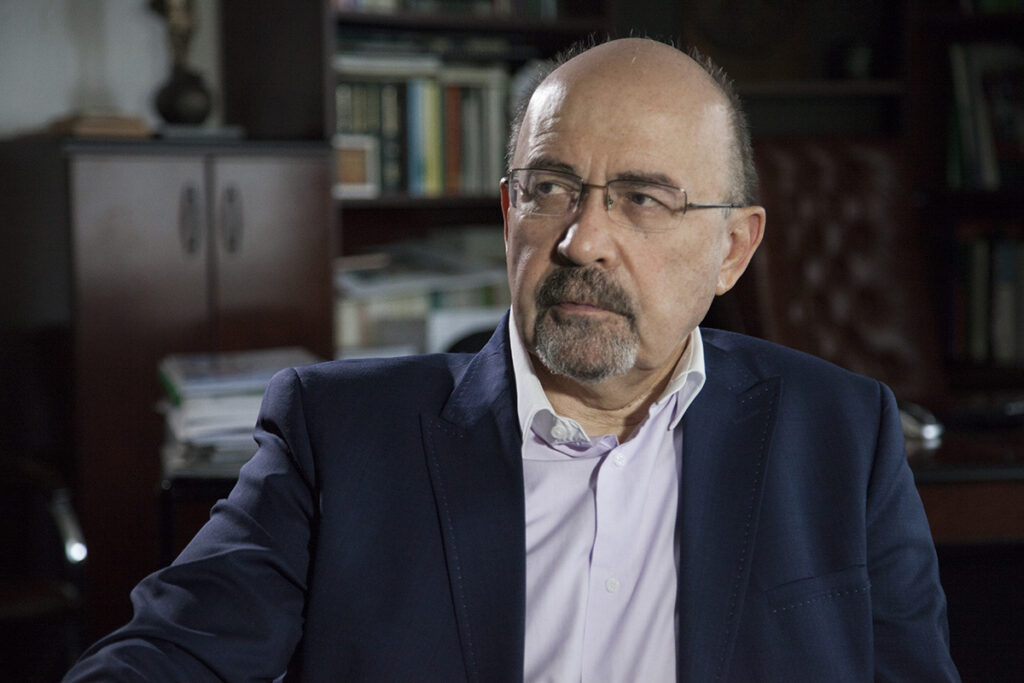

Transylvanian politician and writer Béla Markó. (photo: Sándor Bereczky)

TN – Don’t you have a feeling that Markó the poet has been overshadowed by Markó the politician?

B.M. – Most definitely. As a politician, many approached me on the street both in Romania and Hungary, and I am still better known as a politician. But if at least part of this fame is in recognition of performance, then it’s not a bad thing. A poet is happy if 50 people turn up at his book presentation, while tens of thousands listen to a politician.

This, however, is not a measure of value, only a temporary order of preference. A poem does not change our lives in a spectacular manner, whereas a political decision does. When I returned to literature, I had to get re-acquainted with this, and furthermore, it bothered me that when reading one of my poems, people saw the politician in me, as if I was doing something indecent by writing poetry. But now, I know that my political experience can be beneficial to poetry. Others did not experience what I did, meaning that I have a specific message, maybe even a specific style as of late, when I write something.

TN – You received the MUOSZ prize primarily as a publicist. With an intimate knowledge of the corridors of power, your analyses have surgical precision and keen observational qualities. But do people really listen?

B.M. – The best Hungarian poets and writers also wrote journalism. Our most influential publicist was the poet Endre Ady. Regardless of the fact that I was a practicing politician and held various important offices, I think any true intellectual must say his opinion about what’s going on around him. In speech or in writing, to each his own. What I have to pay attention to is that this must not be just a token action and that I should no longer express myself as a politician. Today my place and role in society is a different one. They do listen to me; many ask my opinion and I do attend political meetings, but obviously, it is no longer me making the decisions, and naturally, I don’t always agree with those decisions.

TN – You lived about half of your life under a dictatorship tempered by endemic corruption and the second half in a kleptocracy tempered by the same all-pervasive corruption. In retrospect, which one was better?

B.M. – Dictatorship not only robbed us of our wealth but of our freedom, too. It robbed us of the freedom of expressing our opinion, the freedom to disagree, the freedom of choice and the freedom of movement. The current Romanian system can be termed a kleptocracy as well; it does have its share of autocratic elements and this is very dangerous, but it still cannot be compared to what was before.

Transylvanian politician and writer Béla Markó. (photo: Sándor Bereczky)

TN – Your political career and fairly large literary oeuvre have presumably taken up most of your time so far. Is there something or are there some things you wish you had more time for?

B.M. – Alas, I am a workaholic. Maybe not because I like work so much but because achievement is important to me, be it a political result or a new poem. Maybe I should tell myself to slow down, even stop and take a good look around. But this won’t happen anytime soon. There is, however, a third calling besides politics and literature, which is linked to both: that of the chronicler. I do regret that I still wasn’t able to recount all that has happened to us, and while there are some interview volumes or discussion books featuring me, I should write my own subjective chronicle. Some of it is already there in my essays and journalism, but not all of it.

TN – Stupid question, but it must be asked: Are you optimistic regarding the future of the ethnic Hungarian minority in Romania?

B.M. – I am hopeful still. But I am no longer quite as optimistic as I was 10 or 20 years ago, when it looked like, step by step, we could achieve all our goals. In the past decade, nationalism has flared up again across Europe, especially in the former socialist countries.

If we look back, we managed to incorporate in the (Romanian) constitution almost everything we wanted in terms of education and language rights, but laws are lately not being observed. If we look just at the legal rights, we could indeed have reason for optimism. But without democracy, minority rights have little meaning. But anyone who knows how hopeless the situation was here in 1989 compared to what it is now — including the situation of the Hungarians — cannot be pessimistic.

Title image: Transylvanian politician and writer Béla Markó. (photo: Zoltán Rab)