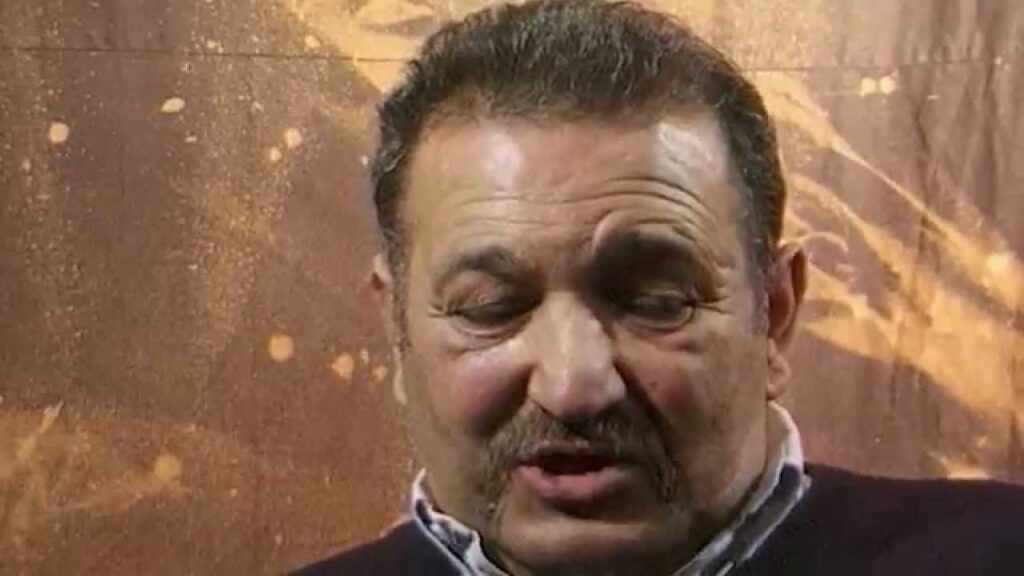

On the occasion of International Roma Day, celebrated on April 8, the municipality of Budapest named a square after Béla Puczi (1948–2009), an ethnic Hungarian-Roma from Transylvania who saved the lives of many Hungarians during the Black March of 1990 in Marosvásárhely, the transindex.ro news portal reported. Puczi is widely viewed as a public hero, as he and his companions courageously defended Hungarian demonstrators against a riled-up and enraged Romanian crowd that was about to lynch them.

The square named after Béla Puczi is located in the vicinity of Budapest’s Nyugati Pályaudvar (the Western Railway Station). Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony put forth the proposal at the request of several Roma organizations, and “the idea was very well received,” transindex.ro wrote.

Béla Puczi was one of the Hungarian-Roma who defended the Hungarian protesters during the violent ethnic conflict that broke out in March 1990 in Marosvásárhely. The ethnic riot that claimed the lives of five and left hundreds wounded is commonly referred to as Black March. This was also the event that left the popular Transylvanian Hungarian writer András Sütő blinded.

The background of this bloody Hungarian-Romanian conflict, which turned the inner city of Marosvásárhely into a battlefield for days, is still unclear in many ways; seemingly, the riots were triggered by the fact that the Hungarians in Marosvásárhely organized a demonstration for the right to educate Hungarian children in their mother tongue. In response, the extreme-right, ultra-nationalist Romanian organization called Vatra Românească, likely with the support of government authorities, transported Romanians from the nearby rural areas to Marosvásárhely, who then ravaged the city center and attacked the Hungarian protesters. Eventually, the riots ended on March 21, when many Hungarians arrived in Marosvásárhely from the surrounding settlements and drove the enraged mob out of the city. Thereafter, the Romanian army restored order.

“Do not be afraid, Hungarians, the gypsies have come!” – That was the encouragement Puczi and his companions shouted to the Hungarian demonstrators encircled by crowds of enraged Romanians, armed with sticks and stones. His sentence has since become a catchphrase.

A few days after the bloody events that took place on the streets of Marosvásárhely, primarily March 19–20, Béla Puczi was detained for questioning by the police. He was beaten for seven days during the interrogation. On the seventh day, he and his companions were transferred to the Marosvásárhely prison, where they were put in pre-trial detention for nine months. The beatings stopped (as Puczi later recounted, one of his companions was beaten to death), but Puczi was interrogated on a daily bases. The trial began in January 1991, and on May 28, 1991, Puczi was sentenced to one year and six months of prison for acts of hooliganism. Furthermore, a fine of lei 600,000 was imposed on him for damaging Romanian state property.

Eventually, due to the intercession of the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (known by its Hungarian acronym of RMDSZ) and the diplomatic pressure of some international organizations, Puczi was released on parole. Fearing further retaliation, he fled to Hungary and applied for political asylum. He went through the Bicske refugee camp and all the offices of Hungarian asylum clerks, but his case was dragged out.

Source: ciganymisszio.reformatus.hu

In 1993, he traveled to France and applied for political asylum there too, but he was refused and officially expelled. He lived in France as an illegal immigrant for years with other Hungarians, Romanians and gypsies from Romania and Hungary at railway stations and in caravans near the vicinity of Paris.

As the mult-kor.hu history portal wrote in a piece, while in France, Puczi was in constant contact with a part of the Hungarian elite living in Paris and told them his story over and over again, hoping that his legal status would somehow be settled. When he returned to Hungary from Paris, he believed he had to hide from the Hungarian police because he still had no refugee status. He only found out that he had, in fact, been granted political asylum a year prior to his return upon a routine police certification.

After 20 years filled with struggles and bitterness, Béla Puczi died in Budapest in 2009 as a sick, homeless man, leaving behind the myths he had about his Hungarian identity and Hungary, mult-kor.hu wrote. As he had lived for a year in a room at the Roma Press Center in Budapest, the staff conducted a 20-hour interview with him, based on which a book was published. In this interview, Puczi told the story of those three bloody days of Black March in 1990, from his and his companions’ perspective.

In 2010, József Lőrinczi, József Sütő, József Szilágyi, Péter Kis Szilveszter Péter, Árpád Tóth and Béla Puczi were honored at a commemorative event organized by the Hungarian government in the House of Terror Museum in Budapest. The latter three received a posthumous recognition. In his speech, the Chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights, Minorities, Civil and Religious Affairs, Zoltán Balog, pointed out that with this occasion of remembrance, Hungarians began to repay 20 years of debt to these brave people who paid a great price for their heroic deeds.

The events of Black March were widely covered in Romanian and Hungarian media, and in the foreign press as well. The role of the Romanian government is still unclear. It is likely that the riots were provoked by the men of the former Securitate (the Secret Service of the communist regime) to justify the need for the establishment of the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI), which was set up a week later, and also to divert public attention from the real problems the country faced after the regime change. Whatever the case, no ethnic Romanian instigators or perpetrators were held accountable for what happened during those days — only Hungarians and Roma were convicted.

Title image: This memorial plaque of Béla Puczi was unveiled in 2017. It is placed on the wall of the Budapest Nyugati Railway Station, facing the parking lot. The inscription says: He and his companions defended Hungarian protesters from the crowds that were set to lynch them.

Source: wikipedia.org