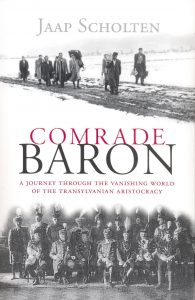

Exactly 70 years ago, on the night of March 2 to 3, 1949 all Transylvanian aristocrats – the majority of them Hungarian – had been deported by the Romanian regular and secret police – the Securitate, established by the Communist regime just a few weeks earlier. Between the hours of two and three in the morning all the aristocrats in the country were roused from their beds by armed men and loaded onto trucks. 7,804 people were deported from their homes that night while all their properties were nationalized. Jaap Scholten, – a Dutch writer with a Hungarian wife, living in Budapest – collected the untold stories of these people by interviewing the last living survivors and their descendants and published them in his book titled Comrade Baron.

How did you first hear about the nocturnal mass deportations of the Transylvanian nobles?

In 2006 I was writing an article about illegal logging in Transylvania for a Dutch newspaper and I was talking with a 63-year-old man on this subject in a shabby restaurant in Sepsiszentgyörgy/Sfântu Gheorghe. The man then told me he was an aristocrat and shared his story with me. He was only six years old when during the night of March 3, 1949 he and his entire family had been taken away in the middle of the night from their house. Police roused him from his bed and when he had to go to the loo one of them went with him with a gun at his back. The whole family was deported that night and took refuge in basements afterwards.

“They were dropped from the top of society to the bottom.”

What made you decide to write a whole book about the topic?

As a Dutch I had a general interest in what happened to the nobility after the WWII in Hungary and in Transylvania, and I always thought somebody should write about it, but nobody did. So when I heard about the 1949 nighttime deportations, I just knew that I have to do it. Another reason was that my wife’s grandmother – who was a baroness and had her own stories – died around that time. Even though she was an aristocrat in Hungary and not in Transylvania, she had a very similar fate and – after the Hungarian Communist regime nationalized all of her family’s properties – she had to work for the rest of her life as a cleaning lady in hospitals. But she still remained full of energy with a good sense of humor for which I admired her very much. When she died, I realized that with all these people dying a whole archive of stories was about to disappear. This was the point when I decided to start interviewing people.

How did you start the work?

First I enrolled at the Central European University’s Department of Social Anthropology to learn how to research the topic in a more professional way. I thought an institute could help me show how properly conduct interviews and how to give the book a better structure. And I was right about it, I had very good professors. One of them, for example, a Turkish professor had studied the secret life of the Armenians who lived in Istanbul. And the situation of the Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania during Communism was very similar. These people had essentially been erased from society, and they had to live underground. They were literally living in basements, and had to abandon their peerages, but secretly they still stuck to their traditions, even during the hardest of times. These people were doubly persecuted: first for being aristocrats and second for being Hungarians.

Video: Mr. Scholten is showing what is left from the castle where the book’s main character, Erzsébet spent her childhood.

How many interviews did you conduct?

I interviewed about fifty people. Besides the members of three generations of the noble families, I also talked with researchers, professors and experts trying to get as comprehensive a view on the topic as possible. I found many of young people who – after the Romanian state returned their properties nationalized between 1945 and 1989 – went back to Transylvania, and had the energy and courage to rebuild at least some of their heritage. Then there was the second generation that grew up during Communism, whom I named “the lost generation” because they were already too old and exhausted to rebuild anything. And there was the third – and oldest – generation, which lived through all these things and which still remembered the time before Communism. These people were the hardest to find and I had to hurry because they were passing away even as I did my research.

This was the first part of the interview – for the second part click HERE!

For more information about the book go to: www.comradebaron.com

Title image: Transylvanian aristocrats at a wedding in 1928. (Cover photo of the book Comrade Baron)