Romania is no stranger to interethnic conflict. Consider the March 1990 clash between Hungarians and Romanians that led to the deaths of five people (two Romanians and three Hungarians), and close to 300 injured people. Fears of more conflict emerged in June when an unsolved border dispute between two settlements (Csíkszentmárton / Sânmartin Ciuc and Dărmănești) turned abruptly for the worse when the mayor of Dărmănești took unilateral action based on questionable documents. It shows how ethnic conflict in the region can provoke tensions that then lead to irreversible impact on both the Hungarian and Romanian communities. The series of events also raises troubling questions about double standards in the Romanian judicial system. Read also Part II, Part III , Part IV and Part V.

“Is there in Romania only one law, or two laws: one in Harghita County and another one in Bacău County? Are there in Romania first-class and second-class citizens?” asked Csaba Borboly, president of Harghita County Council, when asked by TransylvaniaNow. We reached out to the mayor of Dărmănești several times, but Toma Constantin wasn’t available for an interview because, according to his secretary, he is on an extended medical leave.

“I’m afraid. We cannot trust the justice system anymore,” a local mother told TransylvaniaNOW, “I have a grown-up son who wants to be there in the first line when it comes to protecting Hungarian rights, but considering that the gendarmerie punishes the participants of a peaceful demonstration and lets the vandals who tore down the cemetery gate go free, I’m getting the feeling that the justice system used a double standard.” She was referring to the fines imposed by the Harghita County Gendarmerie on the vice president of Covasna County Council Róbert Grüman and Borboly, on grounds that the peaceful demonstration of the Szeklers in front of the Úz Valley cemetery wasn’t announced 48 hours in advance, as required by law.

A more serious Romanian–Hungarian conflict was narrowly avoided June 6, the day of the inauguration ceremony. Fortunately, we didn’t witness another Black Spring, but the events showed how half-truths distributed via multiple channels such as the media and social media fuel hate speech and provoke ire among the Hungarian and Romanian communities. It raises tough questions about how it is possible, in Romania in 2019, for an elected official, the mayor of Dărmănești and those backing him, to so flagrantly abuse his power and go unpunished. That’s especially alarming considering that the Hungarians didn’t deny the existence of graves holding the remains of Romanian soldiers. What the Hungarian side wanted more than anything was the Dărmănești mayor’s willingness to discuss the matter and present evidence.

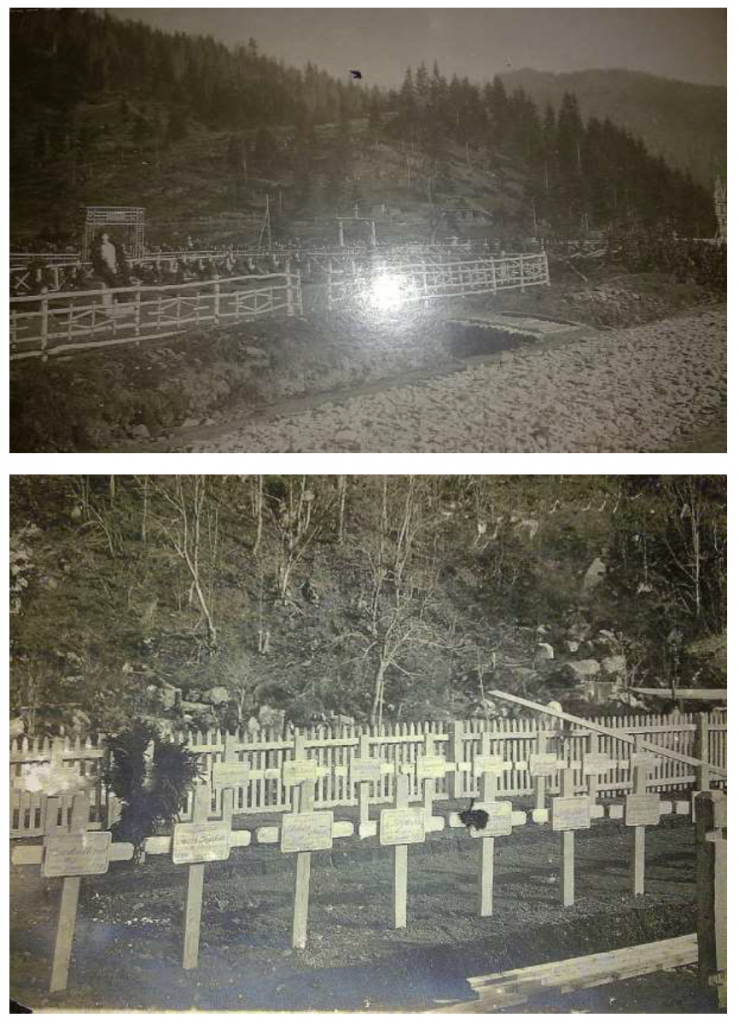

The Úz Valley cemetery was established in 1917 by the Austro-Hungarian army to bury their dead soldiers as the fighting in World War I continued. In 1926 and 1927, the Heroes Cult Association documented the remains of the fallen soldiers at the sight, which saw heavy fighting during the war. According to data published by the National Office for Heroes’ Cult (know by its local acronym as ONCE), this is the time when the Úz Valley cemetery was established. The problem is that there is an older document from 1917 in the Vienna archives that reports the cemetery’s establishment and the names of 600 Austro-Hungarian soldiers buried there. The Heroes’ Cult has data about eight identified and three unknown Romanian soldiers. In addition, they have data on another 847 soldiers, 170 of whom were identified by name, 435 identified by nationality, and 242 unknown soldiers.

During the communist era, it was prohibited to commemorate the war heroes buried in the Úz Valley cemetary, which also led to the sight’s neglect. However, a law passed in 1968 defined the border line between Csíkszentmárton and Dărmănești, which places the Úz Valley settlement in Harghita County and under Csíkszentmárton administration.

”When I saw the situation of the military graveyard at the end of the 1980s, there was nothing there: just a wire fence and a meadow used by locals with a poorly maintained monument,” Csíkszentmárton Mayor András Gergely told TransylvaniaNOW. “Someone without knowledge of the matter said that in 1994 Hungarians destroyed Romanian crosses. That claim has no basis in reality. What was there to destroy? There was absolutely nothing to destroy in that graveyard, because there were no crosses, just two monuments in poor condition. The traces of the graves were visible in spring and autumn, but that’s all.” The mayor was referring to accusations coming from a Dărmănești councilor, who based his allegations on an already debunked article published in Adevarul de Cluj in 1994. In that article, a reporter affiliated with far-right political leaders used the newspaper to misinform Romanians and provoke tensions between the Romanian and Hungarian communities.

Gergely and his team started the restoration works in the early 1990s when he first became mayor of Csíkszentmárton. After 2004 the mayor’s office found partners in NGOs, who helped them continue the work with the support of grants providing funding and human resources.

“In 2014 the Erdélyi Kutatócsoport Egyesület won a grant that allowed us to change the wire fence to a more decent one made of wood. Before that, however, since 2004, based on the map received from Vienna, we mounted the simple wooden crosses without any names on them, because that’s what fits naturally into the landscape, but it has to be aesthetic, modest, and worthy of the soldiers who died here,” Gergely said. “We didn’t make any changes to the original state of the cemetery. Based on the documents we had at that time, the Erdélyi Kutatócsoport Egyesület placed the crosses according to the way they appear in the archive images. We had 600 names that we received back in 1918 from the Hungarian Ministry of Interior. The names of these soldiers appear in the Csíkszentmárton Statutory Register of Deaths,” he added.

Click here to read Part II.

Read also Part III , Part IV and Part V.

Title image: the Úz Valley military graveyard. Photo: István Fekete/TransylvaniaNOW