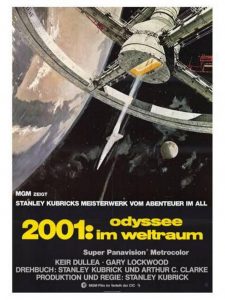

Transylvanian-born György Ligeti. You may not recognized immediately this composer’s name, but you’ve probably heard his music. Stanley Kubrik used his composition in his iconic movie, 2001 Space Odyssey. The interesting thing is that Ligeti was not happy about it at all. He even filed a lawsuit. But why did he do that?

In 1968, when Ligeti had already been living in Vienna for more than a decade, a friend wrote to him from New York to congratulate him for having his music in a very important new Hollywood movie. But Ligeti didn’t know anything about it, so he went to the Vienna opening and realized that, among other works, a lot of his music was used for the film. The only problem was that nobody had asked him for permission. Later he went back to see it a second time with a stopwatch, and found out that more than half an hour of his music, including excerpts from his “Requiem,” appeared on the soundtrack. He sued the film’s distributor, MGM for using his music without permission. The first arrogant reaction he received was that he ought to be grateful to have his music promoted this way. Obviously, he continued the litigation and six years later MGM finally paid him but not much. He received $3,500 altogether, and even this amount was taken mostly by Ligeti’s publishers. In the meantime, the movie became a blockbuster worldwide, and as a result, Ligeti’s work received significant publicity as well. Additionally, royalty from the soundtrack’s sales also began pouring in. In the 1960s, Ligeti was unwilling to write soundtracks for movies, thinking it derogatory for a “real composer,” but his financial problems were solved by Hollywood. Despite their earlier dispute, Ligeti’s music was later featured in other Kubrik movies such as Shine, and Eyes Wide Shut.

So that’s the background story to the soundtrack of one of the (if not the most) important Sci-Fi movies. But who was the man behind its memorable, atmospheric music? György Ligeti’s parents were Hungarian Jews from Budapest, who moved to Dicsőszentmárton (Romanian: Târnăven) in Transylvania – where his father found a job in a bank – during WWI, shortly after their wedding. After the Treaty of Trianon – when Transylvania became part of Romania – unlike many other employees of the bank, though they did not speak Romanian. Three years later, György was born in Dicsőszentmárton and he was six when the family moved to Kolozsvár/Cluj-Napoca. At school he studied in Romanian, German and French, which later became a great asset. (Proving his talent for languages later in the 1960s he even learned Swedish and also English in the 1970s.). Much of his family died in concentration camps during WWII. Only he and his mother survived, and they soon moved to Budapest so that György could study at the Liszt Academy. Among others Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály had influenced the works of the young Ligeti. Like Bartók and Kodály, he also returned to Transylvania and collected Hungarian folk music. But in the long term, he wanted to make his own music and he wanted to compose something radically new. “I was not interested in serial music, in rows. I wanted to develop a very thick polyphonic web. I call it micropolyphony because you cannot hear the individual voices. I wanted a new kind of musical color,” he said in an interview.

In 1956, after the Hungarian Revolution was crushed by Soviet tanks, he decided to leave Hungary and managed to escape with his second wife, Vera Spitz, to Austria under precarious circumstances. They settled down in Vienna, where his life took a 180-degree turn. He had left behind an isolated world in a totalitarian dictatorship and arrived at the citadel of avant-garde music, an environment more conducive to his development as a musician. Although he lived alternatively in Vienna and Hamburg over the next 50 years until his death, he always considered himself Hungarian. According to one story, in September 2000 during a night walk on the streets of Budapest, he asked his Hungarian friend Zoltán Rácz, “Why am I actually living in Hamburg? It is a boring city,” and he then told Rácz that he still dreams and counts in Hungarian. That same year, he wrote a composition (Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedűvel) in Hungarian for the Budapest based Amadinda Percussion Group, led by Rátz. It was the first composition that he wrote in Hungarian since his emigration in 1956, and turned out later to also be his last finished composition ever. Six years later, in Vienna in 2006, he succumbed to a long illness. His grave is in the Wiener Zentralfriedhof, the same cemetery that holds the graves of other great composers, like Beethoven and Schubert.