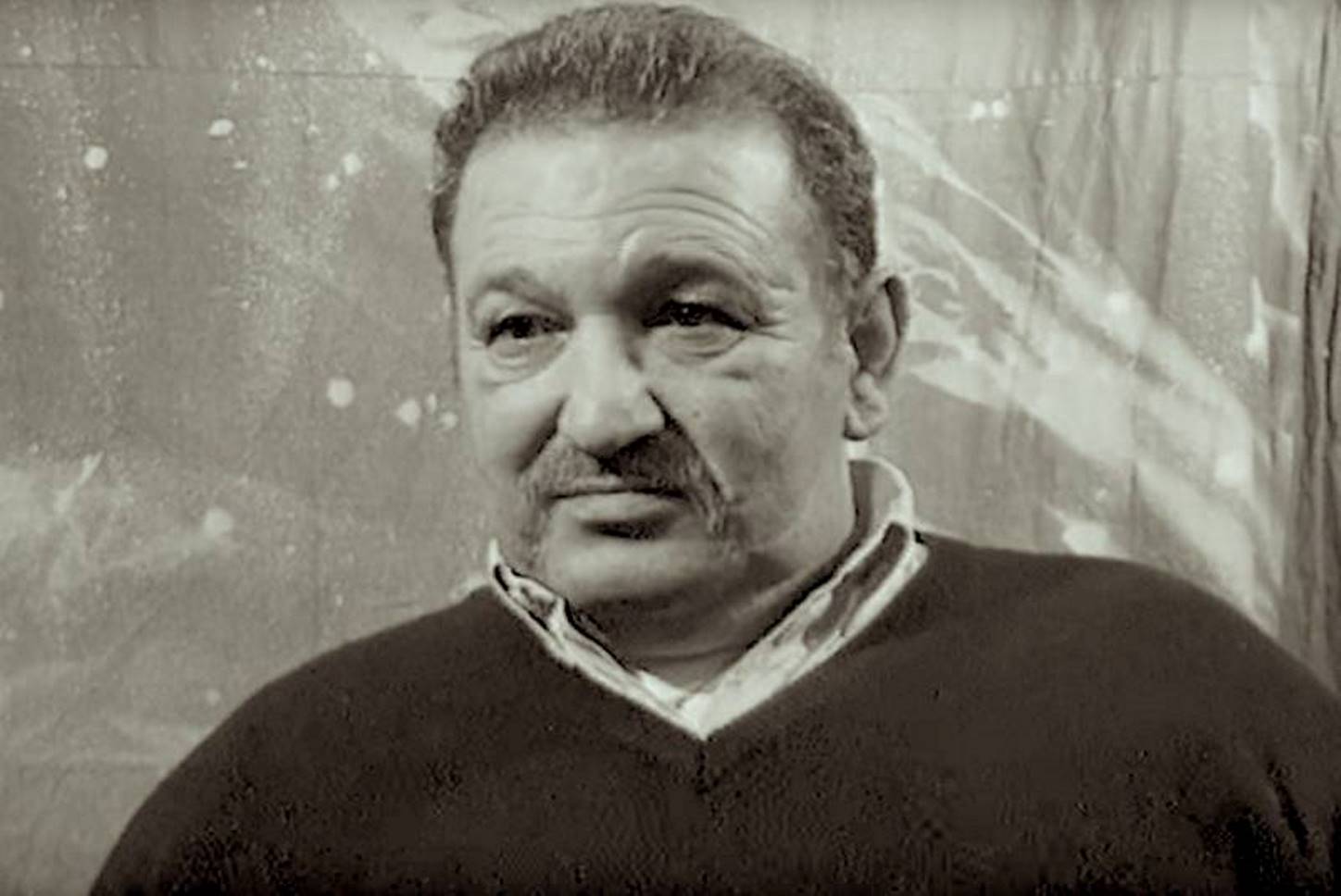

Béla Puczi was one of those white-shirted Hungarian Gypsies who went to defend the unarmed Hungarian crowd – shouting: ”Hungarians never fear! The Gypsies are here!” – during the Black Spring of Marosvásárhely/Târgu Mureș in 1990. A few days after the anti-Hungarian pogrom he was arrested and the thus far ordinary life of the 42-year-old man and father of four rapidly descended into a downward spiral. He was interrogated and beaten for seven days. He spent eight months in jail and was sentenced to eighteen more. He asked for asylum both in Hungary and in France, but never could get back on his feet again and died two decades later as a homeless man in Budapest. Although during his lifetime he never received the acknowledgment he deserved, he received two decorations post mortem and a memorial plaque dedicated to him was also inaugurated recently in Budapest. If we want to pay tribute to his memory or would like to understand the reasons why he and his companions helped to the ethnic Hungarians during the pogrom – and whether he regretted it later or not, after experiencing its consequences – we should get to know his life story.

Hungarian identity rooted in the childhood

Mr. Puczi was born in 1948 in a village near Marosvásárhely, Sáromberke/Dumbrăvioara on the estate of earl Sámuel Teleki. His grandfather was the carter of the countess, while the other family members worked on the fields of the estate. The love for Hungarians was planted in him by his grandfather at an early age: “I learned the most from my grandfather. I heard about the Hungarian nobles, and the names of true Hungarian men from him first”, he said in an interview in Budapest in 2000.

Together with his younger brother, he was raised by their mother after their father left his family. He attended elementary school in Sáromberke, where – along with the other Roma kids – he studied in Hungarian. Later he continued his studies in the economic vocational high school located in the former Teleki Castle. (“Former” because in March 1949 all properties of the aristocrats were nationalized in Romania during one night, including the Teleki Castle as well.) Besides his mother, his studies were supervised also by his grandfather. “…I went to play with the other kids for an hour or two, then he sent for me, to go back home to study”- he said.

“My whole family was proud of me that I was studying. Me and another child became the first Gypsy skilled workmen in the village”

His Hungarian identity was also strengthened by the fact that the other Gypsies living in the nearby villages (Erdőszengyel/Sângeru de Pădure, Marossárpatak/Glodeni, Gernyeszeg/ Gornești) and speaking both Roma and Romanian also considered them Hungarians. They would call them “bozgors” just like the Hungarians. (“Bozgor” means “stateless” in Romanian, and it is a term used by Romanians for Transylvanian Hungarians as a pejorative.) “Every Gypsy in our village spoke Hungarian so the Romanians and the Romanian Gypsies either called us Hungarian Gypsies or bozgors.”

Working in Lebanon

After finishing school, he moved to Marosszentgyörgy/Sângeorgiu de Mureș in order to find a better paying job. He worked in different factories as a driver and he also met there his future wife, Mária Barabás with whom he started a family and raised four children. In order to support them he spent six months each year – from 1982 for the following five years – in Lebanon working in the oil industry. Thanks to this, the life of the family improved, and a three-room block house apartment was allocated to them by his company. During the Romanian revolution he was in Bucharest with his family, and he was also out in the streets demonstrating against Ceaușescu’s dictatorship: “One night, when a truck arrived with free Christmas trees from Brassó/Brașov, I helped hand them out to the poor”, he said.

Black Spring and its consequences

Puczi moved back home to Marosszentgyörgy with his family in the beginning of March 1990, only a few weeks before the pogrom. He was arrested by the Romanian authorities on 28 March and his interrogations – accompanied by heavy beatings – lasted for seven days. On the seventh day Puczi and his companions were relocated to the Marosvásárhely prison, where he was incarcerated for another eight months. While the beatings didn’t continue, he was still interrogated on a daily basis. After his trial in Nagybánya in 1991, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison and had to pay a fine of RON 600,000 for damaging state property.

Downward spiral

With the intervention of international human rights organizations and RMDSZ (Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania), Puczi was released on probation and this was the time when he decided to leave his home and family behind and to claim political asylum in Hungary. But his tragedy was that the Hungarian authorities of the time – only seeing a Romanian Gypsy in him – rejected his claim and told him he could not provide satisfactory reasons to support it.

After being refused refugee status in Hungary he requested a passport and emigrated to France in 1993 and tried to claim asylum there, but was rejected again. In spite of his expulsion, he stayed in Paris and sustained himself with odd jobs but was later arrested and expelled from France. When he arrived to Budapest Airport, police were already waiting for him and was ordered to leave Hungary in 30 days. But he stayed and hid instead. Years passed by like this, when eventually he found out accidentally – during a routine identity check by the police – that his refugee status has already been approved a year earlier. In the late ’90s, after realizing he didn’t have to hide anymore he started to work legally for the Roma Press Center in Budapest, but he never really could get back on his feet again, and in 2009 – at age of 61, far from his home and family – died as a homeless person in the heart of the Hungarian capital.

Legacy

While in his lifetime he never received any official recognition for his bravery in defending the Hungarians, he received two post mortem Hungarian decorations in 2010, in Budapest. In 2017 a memorial plaque was also inaugurated on the wall of the Western Railway Station in his honor, the very place where he lived his last years as a homeless.

Title image: Béla Puczi memorial plaque in Budapest, on the wall of the Western Railway Station.