Unmarried and widowed women belonged to the most vulnerable social categories in the 18th century: it did not take much and they just found themselves standing in front of a judge, facing all kinds of punishments, amongst them the capital one as well. Historian Andrea Fehér had researched hundreds of judicial records of the court of Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca, Klausenburg), dated in between 1712–1799. These historical sources show quite peculiar and startling aspects of the societal life in the 18th century, of the value systems of the age and very sad destinies of several women. The historian outlined her research at a presentation organized at the Hungarian Historical Institute of Kolozsvár, as part of the program of the 10th edition of the Hungarian Cultural Days.

The historian began this research after she had come across an interesting story in the notes of a doctor: it referred to a woman burned at the stake because she had dressed up like a man for two decades, thus “requisitioned rights and possibilities” only open to men. During that age clothes made the man: garments spoke of one’s gender, origins, social status. The most cases of women dressing up as men were recorded in Holland though.

In the 18th century Transylvania women mostly faced allegations as harlotry, infanticide, fornication, adultery or witchcraft. Interestingly enough, in Scandinavian countries wizards were accounted for as well.

Informants and accusers in the judicial documents of the Kolozsvár court were also mostly women, whilst the judges only men. In general, it was not a hard task for judges to state the offences that were said to be committed by the denounced: in the first half of the 18th century judges referred in their decision mostly to previous cases and experiences not as much to the letter of the law. Judgments came easily, on the other hand in some cases the judges showed indulgence as well: sometimes they had listened to the appeal of family members, took into consideration if the accused had children.

For the indictment of fornication it was proof enough if a woman had been seen talking to “outlanders”, who were mostly soldiers, mercenaries who loitered around in the city – said the historian. The first time punishment mostly consisted of threats and warnings, but in case of the recidivism in the crime – which happened quite often – came the punishment of bashing, then the expulsion from the city. If the woman came back, she was mutilated or burned with hot iron.

According to the value system of the era, fornication was a greater sin if it was committed by a woman. They acted against the law of nature as they were the ones who could have got pregnant, thus “bringing strange blood” and shame to the family. Likewise, an adulterous woman faced the danger of capital punishment, and could have literally lost her head. It is true though that in several cases the judge eased the ultimate punishment with regard to the woman’s young age, illness, or the fact that she had to take care of an infant.

The character of the judge was quite a relevant factor, as the bidding of the woman’s children, or other family members were taken into account by many of them. Even so, women were definitely at the mercy of this man-ruled world, and one of the main pillars of the strict societal order was the institution of marriage itself. In some cases this institution became a prison for a woman; that is the explanation for some really cruel cases of wives murdering their husbands, or their newborn babies.

A maiden who got pregnant had not much chance for surviving in this society. That is why some of these young women tried to conceal her pregnancy, or even tried to dispose of the newborn. For instance, in the reports researched by the historian one maiden was denounced by her neighbor, the other one by her landlady. In another case a dead infant was found and local authorities interrogated every maiden in Kolozsvár. They were able to found the mother when they presented her the child’s corpse. Abortion had usually the same punishment as infanticide – but only if the fetus had already “received a soul”, which was thought to happen beginning with the fourth month of pregnancy.

If a woman was married, it was unimaginable that she would not want children – the widely accepted approach was, that they would make an attempt against their child’s life only if they were insane. Women trapped in marriages sometimes tried, and sometimes succeeded murdering their husbands. The judicial documents of the local court tell several stories: there was a woman who tried to poison her husband three times. If the attempted murder was unsuccessful, the wife usually got the punishment of bashing so they seemingly took that into consideration…

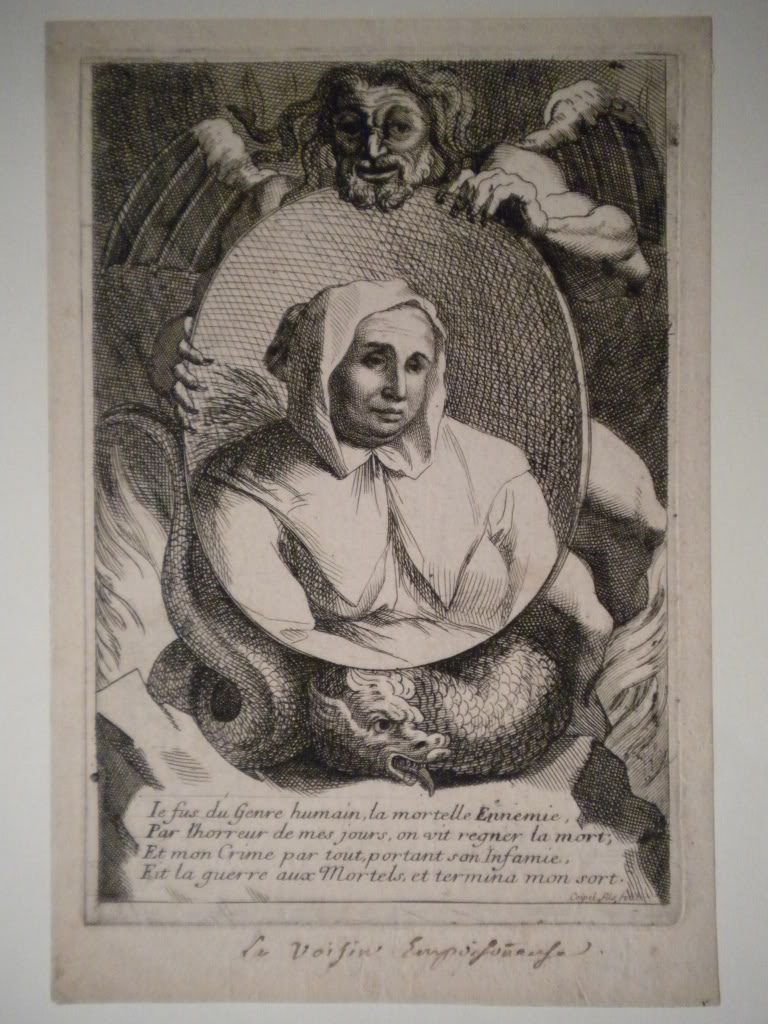

Illustration of a witch. It portrays Catherine Deshayes alias La Voisin, a French poisoner. She was burned at the stake.

Source: wikipedia.org

Throughout two centuries there were 89 witch trials in Kolozsvár, but “only” in 20 cases did the accused receive capital punishment: 18 women were burned at the stake, two were drowned. One could say that Transylvanian “witches” were always women; mostly old, widowed, grumpy women, who has some healing knowledge and could help delivering babies as well. In several cases they misused their status, and even threatened to curse a family that did not call them to be their midwife. They were the “problematic” women in a society in which cause of disease was not linked to the lack of hygiene but to hexes and curses…

Update: Romanian woman burned alive for witchcraft

Title image: Illustration of an interrogation at a witch trial in Transylvania

Source: mol.gov.hu