In his 1889 essay, “The Decay of Lying,” Oscar Wilde opined that “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” It is neither our place nor our calling to be the arbiter in the philosophical debate of Aristotelian mimesis versus anti-mimesis, so without further ado, we give you the abbreviated account of a somewhat unusual – but not overly unusual – Central European life. You be the judge whether art imitates life or the other way around.

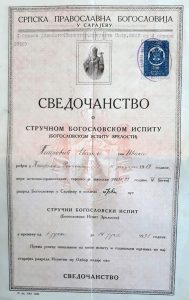

The protagonist of the story is one Evgenije Petrovics of Serbian nationality, born in war-torn Europe in the Hungarian village of Kétfél (now Gelu, Romania), January 10, 1915. Orphaned and adopted during the war, he lived in his native village until entering an Orthodox seminary in Sarajevo, Serbia, from which he graduated in 1935.

By that time – as presumed from his early years in the multi-ethnic Bánság (Banat) region and witnessed by his graduation diploma – he spoke at least four languages. In addition to the four, in the seminary he also studied Greek, Latin and Russian.

He then returned to his native Bánság, got married – a necessary condition for an Orthodox priest to be assigned a parish – and served as village priest until dislocated by another war, World War II, during which he served as a priest in neighboring Serbia.

The family archives have little in the way of documents from his war years, but we know that the young, athletic and movie star-handsome priest lost his wife after only three years of marriage. There are also some fairly hazy accounts of a tragedy somehow involving the by then widower priest in the death of a beautiful woman and her jealous husband.

After the end of the war we find our protagonist in the Romanian capital of Bucharest, earning his living as a science journalist at the Scientific Publishing House. Anyone even slightly familiar with the region’s communist regimes in Soviet-occupied eastern Europe will wonder how a former priest could have landed in such a position of trust. Unfortunately, we don’t have an answer to that question.

Ever the formidable athlete, he also played as goalkeeper for the Romanian journalists’ national football team. He was also an avid motorist, traveling the length and width of Romania on his prized BMW motorcycle. (Side note: besides its inherent value in an era dominated by Soviet imports, such a means of locomotion was incidentally also a definitive babe magnet).

Génó with the Romanian journalists’ national football team

During one of his road trips, our hero – a bon vivant of the Communist era, if there ever was one – meets a firecracker Transylvanian maid in the early 1960s and after a few years of on-and-off relationship marries her in 1967.

We can only surmise the power of this love, but suffice it to say that he wrote over 500 numbered and meticulously calligraphed letters to his wife while still in Bucharest, sometimes referring back to old ones “as I wrote You in letter number xxx”.

Shortly after their marriage, he abandoned his high-flying metropolitan life and moved to the small Transylvanian village of Madéfalva/Siculeni and spent the rest of his days in loving matrimony. He learned excellent Hungarian and was referred to as “Génó bácsi”, but the Szekler community – probably on account of his Serbian nationality and perhaps even his Orthodox religion – never fully accepted him. Regular as clockwork, he visited the village pub for a shot of pálinka (fruit brandy) every single afternoon, but aside from the briefest pleasantries about the weather, the villagers treated him as a stranger until his death in 1992.

Title image: Génó aged 30 (images courtesy of Tibor Tóth)