There is a joke among Hungarians that goes like this:

Lucifer is supervising the work of his devils in hell and is checking whether they are taking proper care of the captives.

Arriving at the kettle where the Germans boil he asks: “How do you keep them from escaping?” “Easy. These are exacting people following all our rules. We just put up a sign ‘Leaving the kettle prohibited!!!’”

Arriving at the kettle with the Russians he asks the same question. “Even easier. The Russians are always drunk. They cannot even think of escaping.”

At the Hungarian kettle, no sign is seen, nor are they drunk. “And what about the Hungarians?”

“Oh the Hungarians. Whenever one tries to escape, the others pull him right back in.”

Putting this joke into a Transylvanian context, without being Lucifer, the question about Romanians arises inevitably. How are Romanians kept in the kettle? Romanians sit in the kettle together and declare “Hai să ne simțim bine!” (“Lets just have a good time!”).

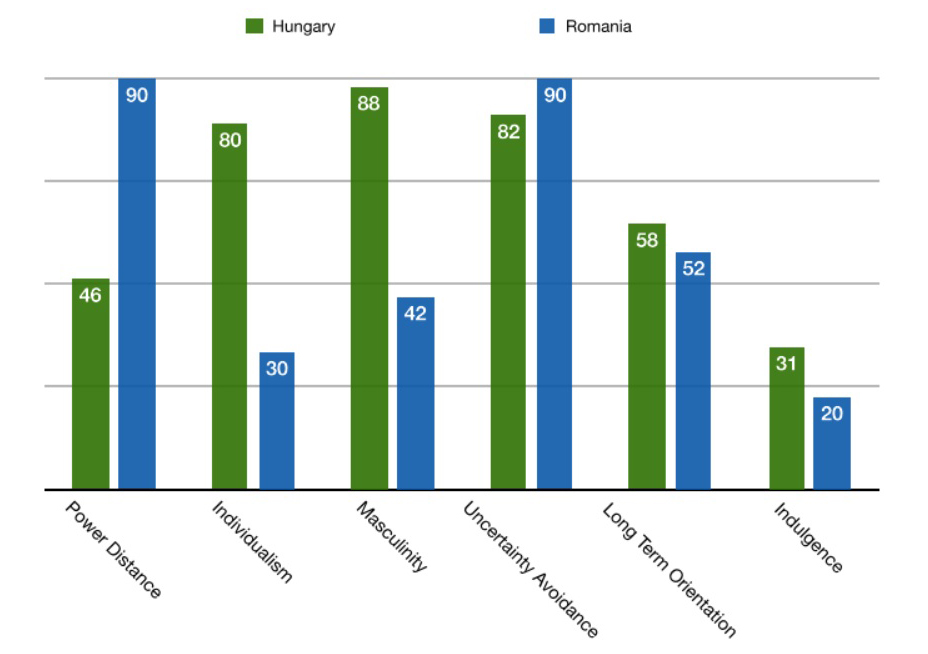

One always walks on thin ice when dealing with prejudices. Nevertheless, there are numerous scientific models to characterize larger groups, foremost from a cultural perspective. The most publicized is the work of Geert Hofstede, a social psychologist, who developed the Cultural Dimensions Theory, analyzing the effect of culture on values and behavior of a given society. The dimensions boil down to six categories:

According to Hofstede´s model, national cultures can be categorized along these aspects on a scale from 0 to 100, helping marketing companies and international business negotiations to understand and communicate efficiently with their target audience.

Returning to the Transylvanian context, how does the Hungarian culture compare to the Romanian culture? When consulting Hofstede´s cultural dimensions one encounters a bleak constellation of starkly contradicting values and priorities.

The first three categories, which are probably most crucial regarding societal and political life, are clearly contradictory. While Hungarians prefer flatter hierarchies where everyone minds his own business in order to be as competitive as possible as a small unit, the Romanian prefers to solve challenges in a collective under a rigid hierarchy, regardless of a competitive result. As if that is not enough to prepare the soil for conflict where these two cultures clash, both Hungarians and Romanians prefer to avoid uncertainty, sticking to their own “truths” as the high score in uncertainty avoidance shows.

Indeed, if one thinks of folk dances for instance, Hungarians are known for the Legényes, an intense individual dance done by young males, while Romanians are often standing in large circles holding each other and dancing in sync. Another example are the highly differing political systems, Romania being designed as a strongly centralized state, while Hungary allows a high degree of autonomy to lower units of administration.

Transylvania as a region has suffered from these contradictions throughout its history, and it is not easy to reconcile such differing cultures. However, if the ambition to create the “Switzerland” of Eastern Europe is going to be any more than just a catchy slogan, both Hungarians and Romanians would do good to take a step back from their trenches, lower their uncertainty avoidance and reflect on the disadvantages and advantages of their own and their neighbor’s culture. Otherwise Transylvania will remain what it is: a Balkans-style, zero-sum game in hell where the one on top dictates the rules of the game.

Title image: Head of Janus, Vatican museum, Rome